In late 2003, the collective American conscious disregarded the war in Afghanistan and observed with intense focus the happenings of Operation Iraqi Freedom, as well as the militant determined to sow chaos within Iraq: Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. Afghanistan was quietly and rapidly becoming a forgotten war. As it happened, al-Qaida central leadership also fostered a voracious interest in the happenings in Iraq. From South Waziristan, paramilitary commander Abdulhadi al-Iraqi coordinated the communications between Zarqawi and al-Qaida leadership1. This proved an exhausting endeavor. An opening for other jihadists to capitalize on the Iraqi’s shift in concern and obtain their own paramilitary success, was also apparent.

For the entirety of the Series, please see – https://chroniclesinzealotry.com/predators-of-the-khorasan/

An Envoy to the Deranged

Zarqawi needed monetary assistance and logistical support from al-Qaida, even though he had yet to officially swear his organization to bin Laden2. In the summer of 2003, word reached Abdulhadi from Zarqawi with a series of requests. Senior Zarqawi lieutenant Luay Mohamed Hajj Bakr al-Saqa (known alternately as Abu Hamza al-Suri and Abu Mohamed al-Turki), sent the message informing that Zarqawi was in need of al-Qaida expertise, personnel, trainers, and finances for his growing insurgency3. Zarqawi focused his personnel needs on explosives and electronics oriented operatives4. Despite some hesitancy5, Abdulhadi initially sent couriers to Zarqawi to act as official representation from core al-Qaida. One courier, Abdullah al-Kurdi, was deemed ineffective, and failed due to his unwillingness and timidness amidst the warfare and subterfuge6. Abdulhadi then turned to a senior envoy in Shakai, the Pakistani Mustafa Haji Mohamed Khan7, better known as Hassan Ghul, to attend to the Zarqawi situation8. Previous Pakistani searches for Ghul, precipitated by American intelligence, had netted several al-Qaida followers, affiliates, and lieutenants, prior to the facilitator’s relocation to South Waziristan9.

In December 2003, Abdulhadi selected, advised and dispatched Ghul on his mission to Iraq10. Ghul was given a phone number by the Egyptian Hamza al-Jawfi, under a false name, in order to contact Abdulhadi in emergencies11. Ghul was to negotiate the redeployment of Arabs and foreign fighters from the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan to Iraq, in order to join Zarqawi. Abdulhadi was dealing with disenfranchised fighters who felt that there was not enough for them to do in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Abdulhadi saw an opportunity to offload some of that dissatisfaction to Zarqawi and provide manpower to a situation that could certainly utilize additional militants12. Ghul was also to ensure that a viable route existed to transplant the fighters into Iraq. To assist with this, logistician Muawiya al-Baluchi was assigned to facilitate Ghul’s path13. In addition, a certain Yusef al-Baluchi also assisted. Yusef had first come to Shakai to sell Abdulhadi on an idea of abducting senior Iranian officials in order to trade for al-Qaida Shura members detained in the Shiite theocracy14. Of note, this idea gained traction later in the saga of the conflict.

Ghul arrived to his destination rapidly. Upon meeting Zarqawi in Iraq during January 2004, Hassan Ghul was treated with an unexpectedly vicious individual. Zarqawi was intent on creating cataclysmic results from increasing violence against Shiite targets15. In the end, a full sectarian war between Sunnis and Shiites would render it impossible for the Americans to control and occupy Iraq. Ghul conveyed to Zarqawi that Abdulhadi would not entertain such a plan16. Abdulhadi was keen on preventing the bloodshed of more Muslims17. Yet there was some cooperation18. Ghul helped facilitate a plan in which Zarqawi would provide Abdulhadi with enhanced weaponry to include potential missiles and chemicals, as well as a promise to attempt to negotiate their differences19. In return, Zarqawi would receive communications equipment and a plethora of experienced fighters who could offer training to his men20. However, Zarqawi balked at the idea of Abdulhadi coming to Iraq himself, owing to the differences in warfare between the two theatres21. Ghul began the return transit to the Khorasan from Iraq with an intended letter for bin Laden, but was subsequently captured by Kurdish forces in Iraq during January 2004 and handed over to the CIA22. A Pakistani of Sindh province, who was born in Medina, he was alternately known as Abu Gharib al-Madani23. American press dubbed him “The Gatekeeper,” and proclaimed Ghul to be among the senior most 20 al-Qaida operatives remaining, with his capture used as validation of the al-Qaida network in Iraq24. However, these reports declared incorrectly that Ghul was apprehended crossing into Iraq25.

Rapidly, Hassan Ghul began interrogation the same month he was captured at CIA Detention Site COBALT for two days. In an episode that would create immense controversy, Ghul was not subjected to any form of torture (or enhanced interrogation techniques), but rather submitted to traditional questioning procedures, resulting in myriad intelligence reports from the sessions26. While initially in Kurdish custody, Ghul was treated as an individual, participating in tea with his captors, leading to informative conversations as opposed to coerced information flow27. During his brief respite at COBALT, CIA officials described colloquially that Ghul “sang” for his interrogators. Astonishingly, in these January 2004 sessions, Ghul provided the CIA all of the basic information they would need to potentially locate bin Laden. As a primary courier himself, he postulated that bin Laden would be residing near Peshawar, in the company of Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti, one of his constant companions and the specific courier that he would be using to message with Abu Faraj al-Libi, his principal manager for the organization28. Ghul predicted that any security apparatus would be minimal, sure to include Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti. This matched Guantanamo assessments, where detainees reported that bin Laden was in the company of Kuwaitis prior to disappearing, and that Abu Ahmed was a functional portion of the network29. According to KSM in his interrogations, Hassan Ghul and Abu Ahmed had worked in tandem to facilitate the transplanting of al-Qaida families from Afghanistan to Pakistan, and that they were working closely together as late as May 200230. Vital for the drone war to come, Ghul repeatedly referenced that Abdulhadi and al-Qaida had established a base in the Shakai valley of South Waziristan31. The Pakistani also outlined al-Qaida leadership structure by informing on Zarqawi, Abdulhadi, Hamza Rabia, Abu Faraj al-Libi, Shaikh Said al-Masri, and other lesser known figures to include Sharif al-Masri, Abu Umamah al-Masri, and the operative known as Abu Jafar al-Tayyar (Adnan al-Shukrijumah)32. Ghul indicated that Abdulhadi was most likely not involved in external operations plotting, but focused on military efforts in Afghanistan, while Hamza Rabia was now chairing such plots33. American media also caught wind of Ghul’s interrogations and the fact that he was delivering information34. Believing that they would miss out on critical information, the CIA transferred Ghul to CIA Detention Site BLACK next and immediately commenced enhanced interrogation in order to prevent Ghul from predicting the actions of his captors, and to glean pertinent data35. The captive began to expectedly deteriorate both mentally and physically, and most importantly provided no additional information of value than what he had given prior on either leaders in Shakai or bin Laden’s courier Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti36.

Based on the information gleaned from Ghul, the CIA put immediate pressure on Pakistan to prioritize the rapid response to the Arabs located in the Shakai valley and within South Waziristan37. Ghul confirmed a significant amount of al-Qaida leadership and affiliates were located in the agency, including the aforementioned leadership structure, plus Khalid Habib, Muhsin Musa Matwalli Atwah, Abu al-Hasan al-Masri, Hamza al-Jawfi, Midhat Mursi, Abu Laith al-Libi, and Tahir Yuldashev of the IMU38. The danger of arrest in the Pakistani cities gave way to encouraging the leadership cadre to live together in the remote tribal regions along the Afghan border.

Despite the failure of Hassan Ghul, al-Qaida leadership reestablished contact with the developing Iraqi insurgency, with the aim of folding them into their movement and network. In fact, Abu Faraj al-Libi also connected with jihadists dispatched to the Arabian Peninsula to commence a militant campaign, forming their own branch of al-Qaida. By the time communication was established, this Arabian franchise was under the command of Abdulaziz al-Muqrin, known to Abu Faraj and al-Qaida leadership as Abu Hajir al-Najdi39– [A]. This preoccupation with foreign theatres allowed for other militants to increase their stature in Pakistan and Afghanistan, and the seemingly forgotten but by no means complete engagement against coalition forces therein.

A Lion Emerges

Principally, the jihadist seen as the most influential during this time may well not have been any original al-Qaida members, but rather a Libyan, whose name became synonymous with the Afghan insurgency against American forces: Abu Laith al-Libi, (Abu Laith meaning father of the Lion). In July 2002, the publicly unknown Abu Laith recorded a telephone interview in which he glorified the militant resistance at Shah I Kot and celebrated what he described as an American humiliation40. Speaking for the insurgency, he readily declared that Mullah Mohamed Omar, bin Laden, and Ayman al-Zawahiri, as symbols of jihad were safe and secure41. He revealed a coalescing of militant elements, confirming warlord Jalaluddin Haqqani, formerly neglected by the Taliban, as now fighting in concert alongside the radicals42. Abu Laith thus emerged into the public sphere of knowledge as a revitalizing paramilitary figure in the war.

Ali Ammar Ashur al-Ruqayi43, was merely 30 in 2002 as he began to coalesce and gather multifarious foreign elements into a distinguishable combat force44. Although an obscure figure at the time, he had the proper credentials for leadership. Having departed his home city of Tripoli around the time he turned approximately 16, Ruqayi traveled to Pakistan and Afghanistan where he trained at the original al-Qaida al-Faruq camp before participating in battles in Khost province, under the command of the venerated Jalaluddin Haqqani, against communist forces45. While he did not officially join al-Qaida, Ruqayi, becoming known as Abu Laith al-Libi, naturally aligned with the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group46. The LIFG, while based in Pakistan, was solely focused on the overthrow of the Qadhafi regime in Libya, and was composed of a multitude of North Africans with this common goal in mind47. During his Afghan service in 1991, Ruqayi met and commenced a lifelong companionship with his future lieutenant, militant Abdullah Said al-Libi48. Within the LIFG, Ruqayi was selected for membership on its Sharia and legal council, in addition to his regular military duties49. Despite a willingness to combat the communists and Soviet forces that had previously been in Afghanistan, by 1993, the LIFG migrated to Sudan, in order to be closer to their homeland targets, and to be further away from the churning firestorm of the Afghan civil war50. Although a Taliban victory just a few years later would cement Afghanistan and the tribal areas of Pakistan as yet again a haven for such militants.

Once in Sudan, Ruqayi received orders for an ever increasingly difficult series of deployments. First, he was trained and given the honor from among his peers to enter Libya and obtain support for the LIFG51. Thus, he traveled to the center of the storm in Libya to assist in instituting LIFG cells, inciting and educating the public in order to accomplish their goals across the country52. Essentially, Ruqayi lectured society and recruits on the reasoning for overthrowing the Qadhafi regime, and ensured their dedication to the cause53. Ruqayi himself was instantly arrested at the border but was able to escape in order to facilitate the spread of LIFG philosophy for a year54. He was brought to a border station after his arrest, but absconded while his guards fussed over his passport and later watched a film55. This incident saw him crossing the desert at night and later supposedly an old minefield56. Poetically, he claimed to have been given water in a dream by the Prophet Mohamed to assist in his journey57. His actions resulted in his family farm being raided by authorities, his father and two of his brothers apprehended58. The brothers later perished in 1996 during prison riots and massacres59.

Afterwards, Ruqayi’s second deployment saw him in Saudi Arabia, using his previously garnered legal expertise to meet and collude with Saudi Islamic scholars60. Ruqayi was seeking justification from these venerated Saudi clerics for LIFG rebellion against Qadhafi, and informing the Saudis of Qadhafi’s crimes against Islam61. The clerics were sympathetic and approved of the LIFG jihad against the Libyan government, going as far as to offer not just their acceptance, but additional instruction directly to the leadership of the network62. For Ruqayi this was a massively successful sojourn, yet it too was fraught with risk. The November 1995 jihadist bombing of the Vinnel Corporation’s training of the Saudi National Guard, resulted in vast numbers of potential radicals apprehended across the Kingdom63. Ruqayi, as a foreign element in the nation, was quickly captured and sent to al-Ruwais prison in Jeddah, notorious for torturous methodologies employed therein64.

What followed for Ruqayi were months of intensive torture, carried out in a variety of ways, leading him to become substantially injured for some time, and precipitating multiple failed escape attempts from the prison65. However, in January 1998, Ruqayi and two other detained LIFG members, were able to take advantage of Ramadan festivities, and jumped from the prison walls due to lax security precautions66. Despite the Kingdom desperately searching for the men, they were eventually smuggled out of the country by old Saudi allies from Afghanistan, who were sympathetic to their dilemma67 – [B]. This led to a third deployment for Ruqayi, this time in Turkey, where he linked with LIFG assets and began to oversee some activities on the Libyan home front68. At this point, Ruqayi was promoted again, to the Majlis ash-Shura of the LIFG, making him vital to the network’s inner workings69. Ruqayi and his fellows were hesitant now in 1998 to migrate yet again back to Afghanistan, despite a government there now amicable to their leadership and cause70. This hesitancy was due to questions of the Taliban’s legitimacy and fear of being conscripted into their campaign against the Northern Alliance71. However, in 1999 the LIFG did in fact transfer themselves into the Taliban nation72.

Ironically, Ruqayi rapidly became a champion for the Taliban and helped to foster a conducive environment among the foreign element jihadists to their rule73. Ruqayi assisted in convincing other Libyans of the value of the Taliban and their hospitality towards the various movements sheltered within their borders74. Otherwise, Ruqayi focused on spurring the militancy of North Africans ever further, primarily from the main LIFG training camp north of Kabul, the Abu Yahya Abdulsayid facility, which he aided in establishing75. Here Ruqayi efficiently prepared class after class of Libyans, Moroccans, and others for jihad in their homelands76. While there were disagreements and differences with al-Qaida, it was not as if Ruqayi and the LIFG were sworn enemies of the network. The overarching disparity was in Ruqayi’s focus on overthrow of apostate regimes in specific countries, while bin Laden and al-Qaida focused on global jihad against all enemies of the religion. Despite this, Ruqayi and his men still cross-trained with al-Qaida, interacted often with their members and students, and made appearances at their camps77.

Ruqayi had found a comfort zone of sorts with the Taliban and Afghanistan. Various foreign militants observed Ruqayi and his influence and status, assuming that he was the actual commander of the LIFG78. Their guesthouse was located within the affluent Wazir Akbar Khan neighborhood of Kabul, giving Ruqayi access to senior Taliban and al-Qaida leadership79. As discussed, this time period was one of great enhancement and rewards for the extremists. They had a valued base of operations from which to prepare for jihad across the planet, but much like other militant leaders, Ruqayi was very wary of an al-Qaida strike on American soil that would indubitably bring the wrath of the US military down upon the Taliban, the jihadists, and their camps, thus erasing years of progress and labor80.

During the initial stages of this inevitable invasion, Ruqayi was assigned by the Taliban to the unenviable task of protecting Kabul from the Northern Alliance and the Americans81. Ruqayi participated in defending the city until its capture, leading a retreat of his fighters and other militants to Khost, instead of Tora Bora82. During this stage, Ruqayi made a name for himself for his defense of the capital and the orderly retreat. He was venerated and coveted by senior al-Qaida for his perspicacity, knowledge, and savviness in battle83. Despite this, his men suffered heavy casualties, and the LIFG was dispersed in disarray84. With a diminished leadership, Ruqayi found himself as the de facto chieftain of the LIFG remnants in Afghanistan85. Ruqayi maintained the luxury of the loyalty of his compatriots. This included several other prominent Libyans assisting him in the insurgency and becoming closely aligned with al-Qaida. The taciturn and tenebrous Abu Sahl al-Libi operated as his primary deputy at this time86. The scholarly Abdullah Said al-Libi and Abu Yahya al-Libi were each poised to ensure the smooth transition of LIFG elements into this new era of jihad, as veterans of the LIFG Legal and Sharia committee87. Yet both were competent in military matters as well and only grew more so under Ruqayi88. Many of Ruqayi’s other comrades and students were killed or captured, to include his own brother Abdulhakim, who fell during the fighting89. Abdulhakim previously recruited for jihadist causes, including a stint in Khartoum, Sudan in the mid-1990s where he indoctrinated potential militants for the cause in Chechnya90. He was known to participate in recreation with recruits, which included kickboxing, although this is probably a euphemism for training regimens at Khaldan or the LIFG camp91. This younger brother, Abdulhakim al-Ruqayi, was slain on the front lines of Kabul92.

Ali al-Ruqayi and his remnants sought a different path to glory. While the Taliban was content with retreating en masse to fight another day (as they had displayed by abandoning their cities), and several al-Qaida factions had fled to Pakistan, Ruqayi’s contingent was determined not only to remain in Afghanistan but to develop a coherent insurgency. This decision was made from a rallying point in the Zormat district of Paktia province, leaving Abu Laith al-Libi as one of the most capable militants based in country93.

Ruqayi now became an invaluable asset for Abdulhadi al-Iraqi and al-Qaida in the aftermath of Shah I Kot and the death of Mustafa Fadhil. Even though Ruqayi and his men were not sworn al-Qaida, they were well trained, and an inherent part of the jihadist resistance, coveted for their expertise and dedication. As such, in whatever direction he turned, a sizable contingent of others joined the Libyan. These insurgents, al-Qaida or otherwise, were disparate, yet shared common goals and rapidly became enmeshed with one another.

Interoperability was vital in the insurgency, allowing Abdulhadi, the Taliban, the Haqqanis, and the Libyan contingent under Ruqayi to labor in step with one another. Interestingly, Abdulhadi could easily be eclipsed by the rising Abu Laith. While the idea of Ruqayi as a resistance captain was not a mere façade, it was romanticized in the fact the he was seriously wounded at Shah I Kot, resulting in he and his men withdrawing from the theatre entirely. The safe havens and holds of Wana, South Waziristan protected the militants, and suffice to say that Ruqayi and his men received the care and quiet they needed to heal and become robust yet again94. Ruqayi lived and healed under the protections of Nek Mohamed Wazir in South Waziristan and the Haqqani Network in North Waziristan. The respite was but brief, and by July 2002, Ruqayi was returning to the field of battle. Herein he gave the telephone interview in which he taunted American efforts95. In doing so, he assumed the mantel of a general of sorts for all of the jihadists. Al-Qaida saw this as a benefit and was aware of Ruqayi’s inclusiveness; all factions were welcome to fight together against the Americans. Al-Qaida, viewing itself as the overall leading organization of the resistance, greatly coveted Ruqayi and his prowess. The experience at Shah I Kot further enmeshed Ruqayi and his fellows with al-Qaida fighters and militants from other foreign element networks96. Abu Jihad al-Masri, an Egyptian militant from the organization Gama’a al-Islamiya, but who was closely allied with Dr. Zawahiri, was dispatched by al-Qaida to enfold Ruqayi into the al-Qaida chain of command97. He was joined in the venture by Egyptian al-Qaida militant Abu al-Hasan al-Masri, who was now acting as deputy to Abdulhadi98. The Egyptians attempted to convince their counterpart based on commonality, a sense of purpose, and that other disparate groupings had already aligned with al-Qaida99. Ruqayi agreed to engage the enemy under the supervision and authority of al-Qaida, though did not speak for his men or the remains of the LIFG100. This is confirmed by internal al-Qaida communications from Abu Faraj al-Libi101. According to a young jihadist interviewed by Newsweek, Abu Laith lived at a hidden established camp in remote South Waziristan, presumably the Shakai Valley, alongside of such figures as the Egyptians Abu Khabab al-Masri and Hamza Rabia102. The South Waziristan location indicates that the camp was actually the established base of Abdulhadi al-Iraqi103.

The Khadr Incident

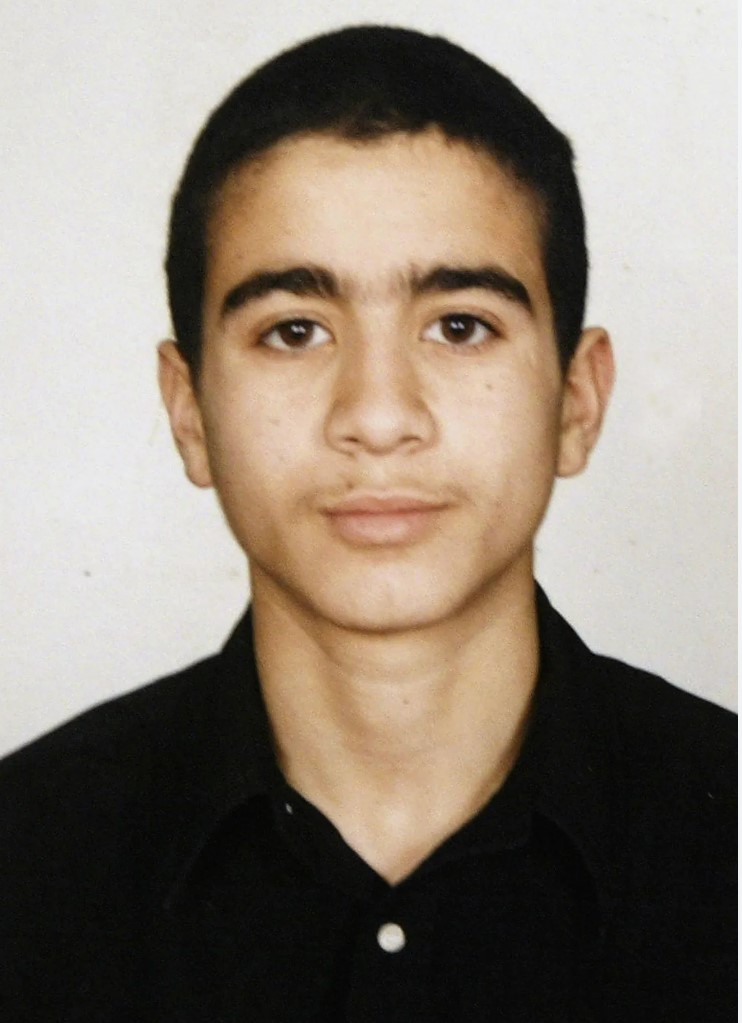

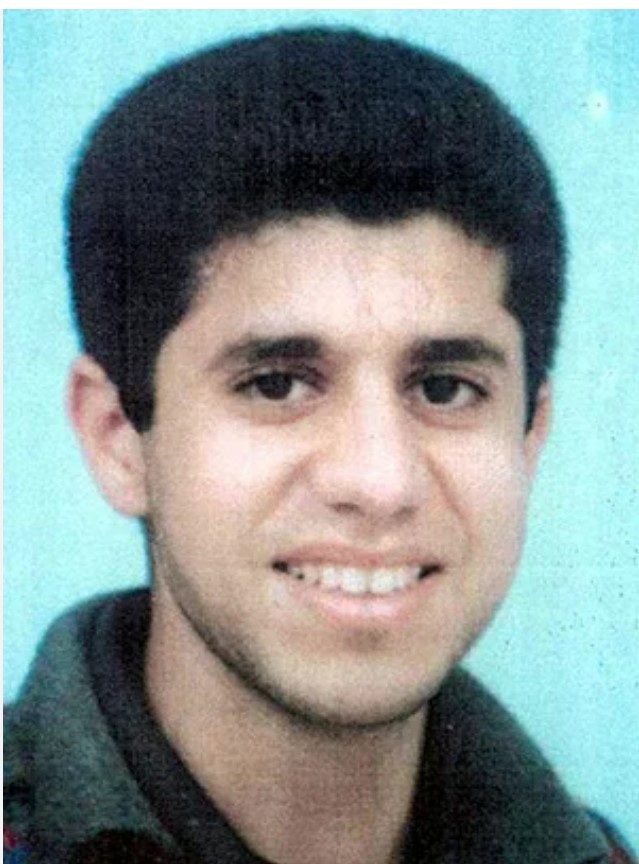

In fact, Ruqayi readily interacted and coordinated with the al-Qaida militants, which included the Egyptian Ahmed Said al-Khadr. Khadr was appointed responsible for coordinating with the tribal forces of the FATA104. With Khadr increasingly focused on his paramilitary responsibilities, his son Omar was deemed the male head of the household, though in reality he was but another child to be cared for by his mother105. The 15 year old Omar desired to separate himself from the women of the family and establish himself with the jihadists in his new home of South Waziristan106. Imploring his father to allow him to merge with the militants, the elder Khadr acquiesced and Omar’s living quarters were transferred so that he could be with the fighters107.

Preoccupied with the war, Khadr displayed more willingness to allow Omar into harm on behalf of these other jihadists. Ruqayi approached Khadr with a proposition concerning the usage of Omar. Since the young man was fluent in Pashto and familiar with Khost, Ruqayi desired him as a translator and guide within the region, to join with his militants raiding into Afghanistan108. Omar and his older brothers were enamored and infatuated with Abu Laith al-Libi and his life experiences109. Quite easily they fell under his sway, having first met him in the late 1990s in Afghanistan110. Omar received intimate training from the militants concerning weaponry and explosives111. Thus Omar readily joined this expedition when his father gave permission112. Omar translated between Ruqayi and Pashtun members of the IED production cell under Bostan Khan in Khost113. Participating in transforming basic landmines into IEDs, Omar assisted in placing the devices against US forces during the summer114.

His mother noted his increasing absence from South Waziristan, culminating in his disappearance in July 2002115. This corresponded with Omar receiving advanced weaponry training from insurgents and his eventual patrols with them116. As mentioned, in addition to his ostensible role as a translator, Omar participated in wiring and improvising landmines into remotely detonated devices used to target American forces117. A video demonstrated this, displaying Omar as he manipulated and deployed the mines118.

On the morning of July 27, US Special Forces received word of a compound housing militants manufacturing explosives in Khost province. A small team of the Special Forces moved on the structure with Afghan support, and found a unit of militants inside willing to die in a hail of bullets119. Ruqayi was not with his men, but Omar was there, armed and fighting120. The fight was brief and ferocious, resulting in a lull during which soldiers approached, and Omar unexpectedly threw a grenade, mortally wounding a Delta Force medic, Sgt First Class Christopher Speer121. In response, Omar was himself injured, suffering two gunshots to the torso122. With three of his companions killed, Omar was treated by another medic, as Sgt Speer was grievously wounded123. Sgt Speer soon succumbed to these wounds. Omar survived and was eventually transported to Guantanamo in October that same year124. Thus, Omar al-Khadr, the young son of Egyptian-Canadian al-Qaida operative Ahmed Said al-Khadr was captured while under the command of Ruqayi. In the aftermath, US forces came to demolish the compound and discovered two additional militants had been killed in the firefight and buried by locals125. This aside, they also uncovered the aforementioned video tape, containing scenes of Omar on patrol, assisting with improvising the landmines, and patrolling with Ruqayi126.

The elder Khadr was shocked at the incident, and although sick, had to attempt to explain the capture to his family127. No amount of apologies made by Ruqayi were sufficient128.

Afghan Forces Under Assault

Meanwhile, Abdulhadi’s ties to the Taliban compelled him to cooperate with the Pashtun radicals in the insurgency, as more of the interoperability between the militants became apparent. While coalition forces were frequent targets of the paramilitary actions, so too now were the inexperienced Afghan Army units. This signaled that the insurgency was encapsulating the region, and that insurgents were aiming efforts at all adversaries.

Often harassed, these Afghan forces took much of the brunt during the campaign in the border provinces. For example, after some convincing, two of Abdulhadi’s Arabs, Abu Khalid al-Maghrebi and Abu Khalid al-Kuwaiti were assigned to oversee two operations in Khost at the end of 2003129. Upon completion of the first incident, the two Abu Khalids focused their attention on a local adversary. In the Nadirshahkot district of Khost province, they established an ambush on the vehicle of Qudratullah Mandozai, the deputy intelligence director of the province130. Mandozai and four other occupants of his vehicle were killed in the heavy gunfire131. The insurgent unit that conducted the attack was traced to a residence and engaged by coalition forces132. According to reports at the time, the Taliban claimed responsibility for the killing, and three of the assailants were killed in the subsequent operation, including two Arabs133. These were Abu Khalid al-Maghrebi and Abu Khalid al-Kuwaiti134. The former was Mohamed Zarli of Casablanca, who attempted to live in Italy, prior to coming to Afghanistan after the 9/11 attacks135. A series of arrests and safehouse raids in Pakistan precluded his departure to Morocco, and so instead he settled and married into the tribal Pashtuns of the FATA136. After much training and combat operations, he was trusted to lead raids and finally the operations in Khost during late 2003137. The latter was Ali Sanafi al-Shammari of al-Jahra, Kuwait138. He was raised in affluence, married in Kuwait, and had five children139. This prior to his radicalization and commitment to jihad in Afghanistan140. Upon traveling and joining the extremists, his superiors were hesitant to utilize him in a martyrdom situation, but the Kuwaiti was insistent141. After the murder of the deputy intelligence director, the Kuwaiti and Moroccan were unaware that they were discovered by coalition forces in the night, and were forced to fight to the death142. The Taliban claimed credit for the ambush, demonstrating early cooperation between the groups and displaying that Abdulhadi nurtured his association with Taliban military matters143, especially give the trust that the Taliban previously placed in the Iraqi in their fight against the Northern Alliance.

Abu Laith al-Libi and his multi-national lieutenants also retained a local focus on Afghanistan and Pakistan, concurrently marauding along with Abdulhadi’s forces. One of his most staunch allies, Abu Yahya al-Libi, was captured by Pakistani authorities in 2002 and delivered to the American prison at Bagram Air Base144. In Dabgai, Khost, one of his trusted lieutenants, a Saudi named Mohamed Jafar Jamal al-Qahtani, and known as Abu Nasir al-Qahtani, led assailants against the nascent Afghan Army in a foray during May 2003, intent on destabilizing the government efforts of maintaining control145.

Perhaps connected with the above attack was the arrest of an Afghan militant, Mohamed Kamin, who was apprehended on May 13, 2003, at an Afghan military checkpoint in Khost146. Kamin was associated with multiple networks of jihadists, and on the day of his capture was transporting gear for the militants, including a GPS device147. He was known to smuggle weapons from Pakistan into Afghanistan and to provide logistic services. His connections included Ruqayi. Meeting with Ruqayi the day before his capture, Kamin was asked to procure a map of the old Khost air port, in order for Ruqayi to determine the weakest point for attack148. Additionally, Ruqayi offered to send Kamin to an advance explosives training course and to pay him for all casualties inflicted on American or Afghan forces utilizing these skills149. Kamin was unable to make the most of the offer and after capture was transferred to Guantanamo Bay150.

By May 27, 2003, Abu Nasir al-Qahtani received his next orders from Ruqayi, and he was to take a reconnaissance crew into Khost province and surveil the American positions of Firebase Salerno and Chapman Airfield. The entire process lasted five days in which Qahtani took four of Ruqayi’s students of Pakistani and Afghan descent, recruited from local madrassas, to a safehouse, before departing for Afghanistan utilizing a donkey151. They were laden with surveillance equipment and weapons152. Upon arrival in Afghanistan they slept in abandoned houses and burial grounds153. Qahtani and his men asked for directions to the bases, inadvertently requesting information from an Afghan Army member, who immediately went to Firebase Salerno to report the oddity154. On the fifth day of the venture Qahtani and his men hiked around cemeteries and difficult terrain for hours in order to conduct the reconnaissance155. Qahtani, and two of his men briefly videotaped the airfield156. By this point the Afghan military arrived and engaged Qahtani and his men in a brief gunfight157. Qahtani was separated and captured quickly upon running out of munitions158 – [C]. Two of his men, Salim Mohamed and Azimullah did not make it much further before being apprehended, while two others, Mahbub Rahman and Rahmanullah, hid in a local madrassa before being surrounded and captured159. All were in possession of weapons and surveillance gear, leading to Qahtani’s detention at Bagram and Azimullah and Mahbub Rahman’s transfer to Guantanamo Bay160. The latter had even shot an Afghan soldier and civilians on a bus just the month prior161. While Abu Nasir al-Qahtani found himself removed from the battle field on June 1, apprehended and imprisoned by American forces, Ruqayi was not struggling to find foreign jihadists in the Khorasan.

In fact, Hassan Mahsum and his lieutenants, of the ETIM, contracted one of their combatants, Abdulsalam al-Turkistani, to Ruqayi upon the former’s release from a Pakistani prison in 2003162. The Uighur came to Ruqayi with willingness, becoming a consistent comrade, and helped command the paramilitary units during what was called the second battle of Shinkai163.

In the summer of 2003, Shinkai, Khost province became the site of another intense battle as militants rained hell down upon an Afghan military/police unit. Ruqayi divided this platoon of 45 men into four contingents under various leaders and commenced the attack164. Despite being a famed engagement in jihadist media, Ruqayi actually lost 15 men killed, plus one of his best, a Syrian named Abu Abdullah al-Shami, was captured and incarcerated at Bagram Air Base165 – [C]. The fierce firefight received perfunctory media coverage, lasting from August 12 and into the following day166. The engagement was described as al-Qaida militants using a variety of weaponry to brutally assault Afghan border police at their base in Shinkai, near Khost, resulting in two policemen and 13 militants killed, plus two captured167. This description seems to match the battle as described in jihadist propaganda, with one of the captured undoubtedly the Syrian lieutenant. Abu Abdullah al-Shami was alternately known as Abu Moaz al-Suri, and had facilitated a guesthouse in Kabul for Syrian militants training in Afghanistan, thus developing a complex network of contacts168. Shami fighting for Ruqayi exemplified his outreach into the multitudinous cliques of radicals.

Numerous fighters from various foreign elements and jihadist groups absorbed into the combined ranks of Ruqayi were present at Shinkai. Hamza Rabia remarked later to an al-Qaida associate that virtually all of the brothers he knew with Ruqayi in 2003 were lost169. One was Saifullah al-Turkistani, of Hassan Mahsum’s Uighur ETIM radicals, who perished in the engagement170. An al-Faruq camp instructor, Abu Walid al-Mauritani, also assimilated into Ruqayi’s influence, acting then as a trainer for his outfit, was killed171. The Yemeni Sultan al-Ashmuri, came to defend Kabul after 9/11 as Mutasim al-Sanaani, fleeing through Khost and becoming enmeshed with Ruqayi, only to die in this combat172. A Saudi known as Abdullah Salman al-Qathami al-Otaibi (Ibn Harathah al-Makki), a veteran of fighting in Chechnya, was slain, reportedly by an RPG173. From Jeddah, another Saudi, Mohamed Dulaim al-Asmari, known as Abu Ubaidah al-Hijazi, once escaped arrest at the Pakistani Embassy in Tehran, before joining the militant retreat in Zormat174. In Pakistan, he joined Ruqayi but could not escape death at Shinkai175. A third Saudi, Saad Khalid al-Shehri, known as Abu Ubaidah al-Banshiri al-Shehri, came to train in Afghanistan prior to 9/11, and manned a position during Shah I Kot176. In Shinkai he was not to survive another fierce clash177. A fourth Saudi, Mohamed al-Zahrani, known as Sahm al-Taifi sought glory in Kashmir before joining Ruqayi, but only found the abyss178. Another Libyan LIFG member, a close companion of Ruqayi named Ziyad Faraj al-Bah, and known as Asadullah al-Libi, acted as a sort of medic during the engagement179. He too was shot down180. Abu Zakir al-Jaziri, had lived in Spain, but just prior to 9/11 trained under Ruqayi at Abu Yahya camp181. He fought beside Ruqayi along the retreat to Khost, even saving the life of Hamza al-Jawfi along the way182. At Shinkai, Abu Zakir was also lost183. A veteran of the Emirati Air Force, Muftah Said al-Tanaji, arrived in Pakistan after the US invasion of Afghanistan, and joined Ruqayi’s faction as Abu Dujanah al-Emirati184. No amount of respect or experience prevented his demise in the battle185. Abu Abdullah al-Somali fought against the Soviets, and afterwards for warlord Hekmatyar Gulbuddin, before returning to his homeland of Somalia to resist US and Ethiopian influence186. His career was truncated in the mostly forgotten engagement187. Omar al-Haj Hamid, a Kurd from Qamishli, sporting the alias Mukhtar al-Suri, failed to wage jihad in Chechnya, but discovered it on the front lines in Afghanistan prior to 9/11. From there he fought in Kabul and Shah I Kot, before failing to flee through Karachi. His shattered corpse was abandoned in the bullet strewn terrain of Shinkay188. Additionally, Hamza Rabia mourned militants Ghul Pacha and Siraj al-Musawir as among 15 killed around this time, leading to the conclusion that they probably died at Shinkai189.

Zakariya Essabar (Abu Yahya al-Maghrebi), of the Hamburg Cell, sought after by the FBI for his direct connections to the 9/11 plot, fell also during the battle190. He too would eventually disappear from American sites seeking his whereabouts, but was still being sought as late as October 2006191. Essabar represented a clear al-Qaida asset allowed to act and fight on behalf of Ruqayi, which would be unheard if the Libyan were completely outside of direct orders from the network’s hierarchy. The Moroccan had previously acted as an intermediary between Ramzi Binalshibh and KSM192. In fact, Essabar, whom Binalshibh had radicalized in Germany during the late 1990s, was dispatched to Afghanistan to deliver the date of the 9/11 operation to KSM193. This of course, after he had received initial militant training with his Hamburg, Germany associates in 2000194. It is believed that he was an option to replace Binalshibh in helming a fifth squad in the 9/11 attacks, but was denied a US visa195. Thus, Essabar was folded into the paramilitary apparatus. After the invasion, and upon setting up camp in South Waziristan, Essabar became a senior logistician for al-Qaida and foreign elements in Pakistan196. Therefore, the amount of trust that al-Qaida had in Abu Laith al-Libi, and the necessity of the relationship were both strong.

Having chronicled the paramilitary infrastructure and political wranglings of al-Qaida through the beginning of 2004, we turn next to the turmoil facing and caused by the network throughout the remainder of the year.

CITATIONS and SUBSTANTIVE NOTES:

- [A] For more on Abdulaziz al-Muqrin, please see the Chronicles in Zealotry Series: Fugitives of the Peninsula

- [B] Among those facilitating the escape was Saudi al-Qaida associate Fayhan al-Otaibi, known as Abu Turab al-Najdi197. He was later a combat commander at Tora Bora.

- [C] Abu Nasir al-Qahtani was transferred to the prison at Bagram Air Base and held as ISN 1462198; Abu Abdullah al-Shami was also transferred to Bagram and held as ISN 1454199.

- Al Qaeda in the Tribal Areas of Pakistan and Beyond, by Rohan Gunaratna and Anders Nielsen, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, Volume 31, Issue 9, December 30, 2008 / The Man Who Could Have Stopped The Islamic State, by Brian Fishman, Foreign Policy, November 23, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/11/23/the-man-who-could-have-stopped-the-islamic-state/ ↩︎

- The Man Who Could Have Stopped The Islamic State, by Brian Fishman, Foreign Policy, November 23, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/11/23/the-man-who-could-have-stopped-the-islamic-state/ ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Treasury Targets Three Senior Al-Qa’ida Leaders, US Department of the Treasury Press Release, September 7, 2011, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/tg1289 ↩︎

- The Man Who Could Have Stopped The Islamic State, by Brian Fishman, Foreign Policy, November 23, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/11/23/the-man-who-could-have-stopped-the-islamic-state/ ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- The Man Who Could Have Stopped The Islamic State, by Brian Fishman, Foreign Policy, November 23, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/11/23/the-man-who-could-have-stopped-the-islamic-state/ ↩︎

- The Man Who Could Have Stopped The Islamic State, by Brian Fishman, Foreign Policy, November 23, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/11/23/the-man-who-could-have-stopped-the-islamic-state/ ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Treasury Targets Three Senior Al-Qa’ida Leaders, US Department of the Treasury Press Release, September 7, 2011, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/tg1289 ↩︎

- Living Proof of al-Qaida in Iraq, by Jim Miklaszewski, NBC News, January 23, 2004, https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna4043576 ↩︎

- Al-Qaida Captive in Iraq Talking, by Andrea Mitchell, NBC News, January 29, 2004, https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna4100629 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- The Black Banners: The Inside Story of 911 and the War Against Al-Qaeda, Ali Soufan, W.W. Norton and Company, 2011 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Al-Qaida Captive in Iraq Talking, by Andrea Mitchell, NBC News, January 29, 2004, https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna4100629 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Letter from Abu Faraj al-Libi to Osama bin Laden, dated October 18, 2004 / Guantanamo Assessment File, Mohamed bin Moujian, ISN 160, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/160.html ↩︎

- Shahi Kot battle: Interview with Al-Qaeda’s field commander Abu Laith Al-Libi (“the Libyan”), July 10, 2002, https://scholarship.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/eb64e2d5-d0b2-495a-b225-87ee4ea2911f/content ↩︎

- Shahi Kot battle: Interview with Al-Qaeda’s field commander Abu Laith Al-Libi (“the Libyan”), July 10, 2002, https://scholarship.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/eb64e2d5-d0b2-495a-b225-87ee4ea2911f/content ↩︎

- Shahi Kot battle: Interview with Al-Qaeda’s field commander Abu Laith Al-Libi (“the Libyan”), July 10, 2002, https://scholarship.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/eb64e2d5-d0b2-495a-b225-87ee4ea2911f/content ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdulaziz Naji, ISN 744, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/744.html ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- UN Security Council Sanctions List, Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, listed on October 6, 2001, https://main.un.org/securitycouncil/en/sanctions/1267/aq_sanctions_list/summaries/entity/libyan-islamic-fighting-group ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf // as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- Al-Qaeda’s New Leadership, Abu Laith al-Libi profile, by Craig Whitlock and Munir Ladaa, The Washington Post, 2006, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/world/specials/terror/laith.html#top ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf // Al-Qaeda’s New Leadership, Abu Laith al-Libi profile, by Craig Whitlock and Munir Ladaa, The Washington Post, 2006, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/world/specials/terror/laith.html#top ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf // Al-Qaeda’s New Leadership, Abu Laith al-Libi profile, by Craig Whitlock and Munir Ladaa, The Washington Post, 2006, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/world/specials/terror/laith.html#top ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf // as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- al-Harb `ala al-Islam: Qissat Fazul Harun, The War against Islam: the Story of Harun Fazul, Autobiography of Harun Fazul, February 2009 ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf // 9/11 Commission Report, Chapter 7: The Attack Looms, 2004 // Saif al-Adel letter to Khalid Sheikh Mohamed, dated June 13, 2002 ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- The New Al-Qaeda Central, by Craig Whitlock, The Washington Post, September 8, 2007, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/national/2007/09/09/the-new-alqaeda-central/c69e5c83-44c5-45db-bdc1-fbd5bb5c130b/ ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Letter from Sheikh Said al-Masri to bin Laden, dated December 28, 2009 // Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf // BNV? ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdullatif Nasir, ISN 244, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/244.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Hassan Zumiri, ISN 533, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/533.html ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 / Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdullatif Nasir, ISN 244, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/244.html ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Shahi Kot battle: Interview with Al-Qaeda’s field commander Abu Laith Al-Libi (“the Libyan”), July 10, 2002, https://scholarship.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/eb64e2d5-d0b2-495a-b225-87ee4ea2911f/content ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf // as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf // Letter from Abu Faraj al-Libi to Osama bin Laden, dated October 18, 2004 ↩︎

- Letter from Abu Faraj al-Libi to Osama bin Laden, dated October 18, 2004 ↩︎

- The Taliban’s Oral History of the Afghanistan War, by Sami Yousefzai, Newsweek, September 25, 2009, https://www.newsweek.com/talibans-oral-history-afghanistan-war-79553 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- Memorandum for Detainee Omar Ahmed Khadr 0766, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, Office of the Chief Prosecutor, Office of Military Commissions, Notification of the Swearing of Charges, https://www.asser.nl/upload/documents/20120820T103005-Khadr_Sworn_Charges.pdf ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Bostan Khan, ISN 975, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/975.html ↩︎

- Memorandum for Detainee Omar Ahmed Khadr 0766, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, Office of the Chief Prosecutor, Office of Military Commissions, Notification of the Swearing of Charges, https://www.asser.nl/upload/documents/20120820T103005-Khadr_Sworn_Charges.pdf ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- The secret Omar Khadr file, by Michael Friscolanti, Maclean’s Magazine, September 27, 2012, https://macleans.ca/news/canada/the-secret-khadr-file/ // Unanswered questions in 8-year Omar Khadr saga, by Michelle Shephard, The Toronto Star, November 5, 2010, https://www.thestar.com/news/world/unanswered-questions-in-8-year-omar-khadr-saga/article_f53f7d9a-a5fd-5c59-9ceb-18a80950d935.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Michelle Shephard, John Wiley and Sons Canada, 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Taliban unit killed after ambush, Al-Jazeera, December 28, 2003, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2003/12/28/taliban-unit-killed-after-ambush ↩︎

- Taliban unit killed after ambush, Al-Jazeera, December 28, 2003, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2003/12/28/taliban-unit-killed-after-ambush ↩︎

- Taliban unit killed after ambush, Al-Jazeera, December 28, 2003, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2003/12/28/taliban-unit-killed-after-ambush ↩︎

- Taliban unit killed after ambush, Al-Jazeera, December 28, 2003, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2003/12/28/taliban-unit-killed-after-ambush ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Taliban unit killed after ambush, Al-Jazeera, December 28, 2003, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2003/12/28/taliban-unit-killed-after-ambush ↩︎

- Profile: Abu Yahya al-Libi, BBC News, June 6, 2012, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-18337881#:~:text=He%20claimed%20to%20have%20been,past%20their%20guards%20to%20freedom. ↩︎

- Defense Intelligence Agency Terrorist Recognition Cards, Abu Nasir al-Qahtani, October 2006 // Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Mohamed Kamin, ISN 1045, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1045.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Mohamed Kamin, ISN 1045, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1045.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Mohamed Kamin, ISN 1045, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1045.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Mohamed Kamin, ISN 1045, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1045.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Mohamed Kamin, ISN 1045, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1045.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Azimullah, ISN 1050, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1050.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Azimullah, ISN 1050, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1050.html // Guantanamo Assessment File, Mahbub Rahman, ISN 1052, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1052.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Azimullah, ISN 1050, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1050.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Mahbub Rahman, ISN 1052, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1052.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Azimullah, ISN 1050, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1050.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Azimullah, ISN 1050, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1050.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Mahbub Rahman, ISN 1052, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1052.html // Guantanamo Assessment File, Azimullah, ISN 1050, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1050.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Mahbub Rahman, ISN 1052, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1052.html // Guantanamo Assessment File, Azimullah, ISN 1050, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1050.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Mahbub Rahman, ISN 1052, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1052.html // Guantanamo Assessment File, Azimullah, ISN 1050, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1050.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Mahbub Rahman, ISN 1052, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1052.html // Guantanamo Assessment File, Azimullah, ISN 1050, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1050.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Mahbub Rahman, ISN 1052, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1052.html ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- as-Sahab Media Production, Winds of Paradise, Part 3, Eulogizing Abu Laith al-Libi, February 10, 2009 ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- At least 17 killed in Afghan blasts, The Guardian, August 13, 2003, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/aug/13/afghanistan.alqaida ↩︎

- At least 17 killed in Afghan blasts, The Guardian, August 13, 2003, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/aug/13/afghanistan.alqaida ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Mahsum Abdah Mohamed, ISN 330, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/330.html ↩︎

- Hamza Rabia letter to Spin Ghul, dated June 29, 2004 ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- Hamza Rabia letter to Spin Ghul, dated June 29, 2004 ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Defense Intelligence Agency Terrorist Recognition Cards, Abu Nasir al-Qahtani, October 2006 ↩︎

- Martyrs in a Time of Alienation, by Abu Ubaidah al-Maqdisi (Abdullah al-Adam), (book of 120 deceased militant biographies from the Khorasan theatre), 2008 ↩︎

- 9/11 Commission Report, Chapter 5: Al Qaeda Aims At The American Homeland and Chapter 7: The Attack Looms, 2004 ↩︎

- 9/11 Commission Report, Chapter 7: The Attack Looms, 2004 ↩︎

- 9/11 Commission Report, Chapter 7: The Attack Looms, 2004 ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Abu al-Laith al-Libi, by Kevin Jackson, CTC Jihadi Bios Project, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CTC_Abu-al-Layth-al-Libi-Jihadi-Bio-February2015-1.pdf ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Mahbub Rahman, ISN 1052, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1052.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Mahsum Abdah Mohamed, ISN 330, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/330.html ↩︎

© Copyright 2025 Nolan R Beasley