Unyielding dedication to intricate plots to match or supplement the 9/11 attacks left Khalid Sheikh Mohamed in a quagmire of half-constructed conspiracies and idealized, yet inept operatives. In addition to the failed shoe bombers, the most potent examples that embody this concept include Jose Padilla, Binyam Mohamed, and Iyman Faris. The enormity of the misfortunes of KSM drew the ire of his immediate overseer, but the increased pressure along with his overconfidence drove KSM towards even more follow-on operations.

For the entirety of the Series, please see – https://chroniclesinzealotry.com/predators-of-the-khorasan/

Debacle at Mirwais

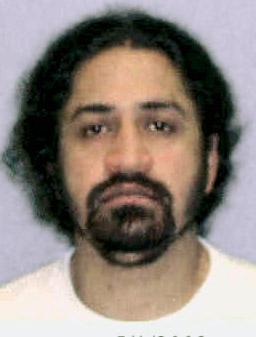

The misfortunes of KSM stemmed from the dearth of capable and viable operatives. Much of this was due to the losses suffered in the early stages of the war. In a famous engagement in the aftermath of the Taliban collapse, KSM was denied the services of a group of his dedicated jihadists. It began with the realization that the defense of Kandahar was untenable. The Egyptian Saif al-Adel ordered the commencement of a slow retreat on November 7, 20011. Among those attempting to flee were ten militants, traveling in two separate cars in avoidance of airstrikes2. Yet this evasion led to collision and the death of one of their number3. The remaining nine were transported back into Kandahar, for assistance and convalescence at the Mirwais, a Chinese hospital in the city4. Awakening there with a broken leg and wounds to his face, was a Saudi militant, Majid Abdullah al-Judi5. The injured al-Qaida belligerents proceeded to barricade themselves within the second floor of the hospital, donning explosives and promising to detonate if attempts were made to capture them6. They also held handguns, and commenced what became a two-month standoff with authorities7. Judi claimed not to be one of the criminals, and that only eight militants were participating, although he himself was most likely the ninth from the accident8. Azmari al-Rahil, the apparent leader of the operatives, dispatched a letter with funds to KSM from the entrapped militants, in order to forward along assistance to the surviving jihadists9. This indicated that beyond the obvious paramilitary services they provided to Saif al-Adel, these militants also were of value to KSM and his plots. Saif al-Adel later lamented leaving behind six of his men in the hospital to be arrested, in the eventual, inevitable raid to liberate the facility10. However, Adel’s numbers were incorrect as we will see.

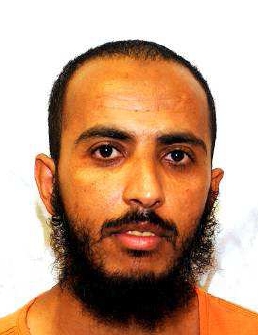

Afghan security forces from the new Afghan National Army supported by American forces neutralized the threat in the hospital on January 28, 2002 after an arduous ordeal11. First however, two of the surviving militants were captured via their only trusted doctor at the facility12. These two were the Saudi Judi, and a Yemeni militant Adam Mohamed Ali al-Awaith, who were taken on December 15 and transferred to US custody on December 2913. ANA officers reported that Awaith, known as Abu Waqas was not captured with a weapon, perhaps displaying that he was unwilling to face martyrdom14. This was most likely attributed to a previous wound, as he lost the lower portion of a leg during the bombing campaign commencing the invasion15. In fact, other reports revealed that the remaining militants were unable to care for Awaith, and were eager to deliver him into the care of the besieging authorities16. Judi, believed to be known as Abu Hamza al-Makki, was captured with several papers indicating that he had received advanced training from Saif al-Adel and his instructors at the Mall Six complex at Kandahar airport17. This clashed with Judi’s cover story, declaring that he came to Afghanistan in mid-November 2001 in order to labor for al-Wafa Foundation in charitable causes, despite the fact that Wafa ceased operations a month earlier18. Judi’s documents revealed a story in which he had already received basic training prior to engaging in the advanced tactics of the Mall Six complex19. Awaith the Yemeni meanwhile, was believed to have been a veteran of training at the advanced Tarnak Farms camp, and thus would have been at least known to senior al-Qaida leadership20. Another of the militants attempted to abscond from the hospital on January 8, and upon being cornered, ended his life with a hand grenade21. This left the militants in the hospital numbered at six, confirmed by press coverage of the event at the time22.

The Afghan National Army reported that the raid began at 0340 in the morning and lasted until the afternoon, with three militants killed by grenades and the other three by gunfire23. Previous attempts to starve the militants by ceasing their food supply were rebuked24. Another plot during the siege to drown them out with water pumps was unsuccessful25. Every attempt at communication was met with more gunfire26. While US Special Forces purportedly acted in an advisory role, witnesses claimed that they were direct participants27. Americans could be heard giving direct orders in the battle, and at least two of the militants were killed by American fire28. One operative guarding the hospital floor during the barricade was believed to be known as Abu Dujanah al-Makki, and was one of those killed in the raid29. He appeared on a future list of 182 killed or wounded al-Qaida militants, while Judi, the captured Saudi, appeared on a future discovered roster of 324 militants that had attended training, resided in guesthouses, and turned over belongings (including passports) to al-Qaida handlers30 – [A]. Azmari al-Rahil, in his letter to KSM, mentioned that he maintained five men, and that all were willing to achieve martyrdom31. As it happened, he and his men were obliged. Of the 100 ANA forces and 20 US Special Forces participating in the raid, only five Afghans were wounded32. The dead militants included Arabs of Saudi, Yemeni, and Algerian nationalities33. Only Judi and Awaith appear in Guantanamo documents as survivors of the incident, indicating that Saif al-Adel was incorrect in his assessment that his six loyalists were captured34. This is but one of several incidents describing how KSM was rapidly losing invaluable experienced and dedicated radicals. Azmari al-Rahil, when facing death, thought to consider KSM and his future needs. Other operatives available to KSM at the time, lacked the same intensity, and when combined with the bluster of their commander, were destined for obscurity and failure.

Collapsing the Bridge

Iyman Faris was born in Azad Kashmir35 in 1969, under the name Mohamed Rauf, and by the early 1990s had militant experience, with training and combat in Afghanistan against the Soviets, Kashmir, and Bosnia36. It was while in Bosnia that Faris assumed the identity of a fellow militant, an Emirati who renewed his visa to the US and gave Faris his passport in order for the latter to gain entry to the country37. Under these false pretenses, combined with persistent perjury, he succeeded in remaining in America, applying or asylum, marrying a citizen, and eventually undergoing the naturalization process in 199938. At this point, he changed his name to Iyman Faris39.

Ostensibly, the Columbus, Ohio based Faris was a diligent laborer, driving trucks for his living40. However, the Kashmiri maintained an interest in jihad, and as such, in 2000, traveled abroad on a journey which led him in a return to Afghanistan41. As a naturalized American citizen he was undoubtedly focused upon by al-Qaida leadership at the camps. In fact, he convened with bin Laden and was given the seemingly innocuous task of researching ultralight aircraft to be potentially utilized by bin Laden as a means of escape42. Faris delved into this information thereafter at an internet cafe in Karachi, before reporting his findings43. Sources also claim Faris became acquainted with KSM in 2000 and 2001, and even provided logistical supplies to the camps, to include sleeping bags and cellular phones44.

In the aftermath of the invasion, Faris, under yet another assumed identity assisted in garnering airline tickets in Pakistan for the exodus of militants45. In the end, Faris became yet another fleeing foreigner linked to KSM in Karachi, destined to be enmeshed in complicated plotting. His status as a truck driver and his access to cargo planes, yielded concepts of hijacking and crashing these larger craft with high fuel capacity46. Faris proposed using his access to airport tarmacs to place a vehicular bomb in proximity to a loaded passenger aircraft47. Faris was dispatched with goals of researching and obtaining the means to derail trains, as well as destroying the Brooklyn Bridge via the severance of its suspension cables48. In April 2002, Faris succeeded in escaping Pakistan and returning to America49. He immediately commenced his online research, focusing on tools known as gas cutters, and even traveled to New York City later in the year to case the bridge50. Despite his research and probable intent, no attacks materialized, with Faris reporting to his seniors and KSM throughout the next year in coded emails, culminating in the realization that “the weather is too hot51.” Faris acknowledged that the plot to collapse the bridge was too far-fetched with limited chance of success52.

American Mujahadin

The saga of Jose Padilla, an American with Puerto Rican heritage, began in Brooklyn with his birth, but he was raised aimless in Chicago53. Despite his mother’s intense Pentacostal religious leanings, and Padilla’s own initial fervent association with Christianity, the youth soon found himself enthralled with gangs54. At merely 14 years of age, he was placed in juvenile detention after he and another wayward delinquent conducted a botched robbery resulting in the stabbing murder of one of the victims55. While Padilla was not the primary assailant, he nonetheless spent the next five years in detention, having kicked the dying man on the ground56. Later, at age 20, a newly married Padilla was in Florida and engaged in a road rage incident involving his threateningly discharging a firearm at a refueling station57. In jail, he eventually attacked a guard, resulting in increased incarceration time. Yet by age 21, he was free and along with his wife worked in fast food, attempting to change their fortunes and lives for the better58. A manager introduced the couple to Islam and they rapidly converted, with Padilla becoming increasingly dedicated, obsessed, but not yet radicalized59. In 1994 he shocked his family by changing his name to Ibrahim, and confounded his wife and friends in 1998 with the decision to transplant to Egypt in order to absorb the culture while teaching English60. His first marriage was left in tatters when he married again in Cairo, engaging in even more traditional Islamic practices and impressing his new wife’s family with his piety61.

Upon completing the Haj to Mecca, Saudi Arabia in March 2000, Padilla declared an intention to next teach in Yemen, and commenced the journey alone62. His new Egyptian family believed the ruse63. Instead, Padilla had actually become acquainted with a member of al-Qaida’s robust Yemeni facilitation array64. During May in Yemen, Padilla dwelled with his recruiter, who convinced his new charge of the merits of training in Afghanistan65. From there another individual took possession of the American in Sanaa and facilitated his travel in June to Quetta, Pakistan66. He took the familiar path of jihadist recruits to Kandahar, Afghanistan and subsequently commenced training67. First, Padilla completed a form required by al-Qaida for all attendees of the camps, known as the “Mujahidin Identification Form,” or “New Applicant Form,” in July68. He identified himself with the kunyas Abu Abdullah al-Muhajir and Abu Abdullah al-Espani69. Padilla went on to describe his language proficiencies, familial and professional history, relevant skills, recent travels, and the ease in which he could migrate to and from America70. After the US invasion, an Afghan militia, aligned with American forces, provided a binder to the CIA containing the document along with multiple other pieces of evidence from raided al-Qaida camps and safehouses71. The CIA gifted the application to the FBI and in December 2001, American authorities knew that Abu Abdullah al-Muhajir was a dangerous homegrown militant72.

Successfully graduating from three months of basic militant and weapons instruction at al-Faruq, Padilla’s entry form had garnered the attention of Mohamed Atef, assuredly due to his status as an American73. Atef expressed interest in ascertaining Padilla’s commitment to religion and cause74. Padilla was aiming to fight in Chechnya75, but Atef looked to redirect the American to al-Qaida operations. The al-Qaida paramilitary superior even fronted the funds for Padilla to return to Egypt in April 2001, under the promise that he would return to Atef76. The American was forced to apply for a new passport in Karachi, which garnered negative attention from both the Pakistanis and US State Department consular employees, who referred to Padilla as “sketchy77“.

In June 2001, Padilla returned to Afghanistan and reconvened with Atef in Kandahar. Later, Atef broached the subject of Padilla conducting attacks in the US, while meeting in the summer78. This plot revolved around utilizing the natural gas supplies of apartment buildings to cause large explosions in the high-rises79. Atef assigned Padilla and Adnan Gulshair al-Shukrijumah to obtain specific advanced explosives training from an expert concerning the plot near Kandahar airport80. They were instructed on how to seal the apartment and set timers for the detonation81. Yet Padilla and Shukrijumah were not compatible, resulting in the aborting of the plan82.

Atef kept Padilla close, even though the American had retracted himself from the plot over reservations of being able to conduct an attack alone83. He remained with Atef through the initial portions of the invasion, and on the night in November in which Kabul began to fall and Atef was assassinated, avoided fate by dwelling in his explosives instructor’s domicile instead84. Yet Padilla returned to Atef’s home in a attempt to extract his superior from the debris comprising his tomb85. Padilla joined a column of foreign element fighters retreating from Kabul to Khost86. Eventually, he was facilitated into Pakistan with the assistance of Abu Zubaydah, whom he rejoined again in Lahore87. Abu Zubaydah and Abdulhadi al-Iraqi had particular plans for the American and other selected operatives procured during the retreat, to include Binyam Ahmed Mohamed88.

A Radioactive Delusion

Binyam was an Ethiopian, who gained political asylum in Britain during the 1990s89. A college educated electronics technician, Binyam eventually fell to habitual drug usage before his radicalization via known extremist communities. Linked with Algerians entering Afghanistan for training, Binyam was diverted to al-Faruq camp to complete his instruction90. He twice received advanced training at the Moroccan Tarik camp in vicinity of Bagram (once alongside Richard Reid), and when the US invasion precipitated the fall of Kabul, fled through Khost to Zormat91. Hundreds of potential fighters coalesced, and while failing to convince paramilitary officials to allow him to participate in the defense of Kandahar, Binyam was noticed by Abdulhadi al-Iraqi92. After examining his passport and abilities, Abdulhadi and Abu Zubaydah offered him a special project, involving electronics schooling across the border and the subsequent construction of remote-controlled IEDs93. Next, in Birmal, he linked with a group that included Padilla, also selected for the tasking94. These two, and two Saudis, were to be the core of the cell receiving the electronics training and providing the future IEDs95. They were funneled into Bannu, Pakistan by Abu Zubaydah, received cursory electronics training, and traversed on to Lahore96.

Eager now to depart Pakistan as opposed to returning to the war theatre97, Binyam and Padilla sought to make themselves worth dispatching out of the area entirely. Abu Zubaydah discussed various operations with them to include utilization of gas tankers as weapons and cyanide attacks on nightclubs98. The two now could guarantee their way home, and as such, researched, and concocted an even more ludicrous machination99. The research was conducted online, drawing from a satirical article, resulting in the strategy to construct and deploy a so-called “dirty bomb,” in which a conventional explosive spreads radioactive materials100. According to the article, the development of a “dirty bomb” was described as possible by filling a bucket with uranium hexaflouride, tying a rope to said bucket, and then swinging it around rapidly in the air for 45 minutes101. An incredulous Abu Zubaydah was unimpressed, dismissive, and bemused by the concept proposal102. Nonetheless, he saddled himself with the two prospects, and a week later displaced to a Faisalabad safehouse, in order for them to receive the much touted electronics instruction103. From there he ridded himself of this issue and dispatched the pair ironically to KSM in Karachi104. Padilla and Binyam departed Abu Zubaydah in March 2002, just prior to the latter’s capture in Faisalabad and subsequent transfer to FBI and then CIA custody105. Attorney General John Ashcroft conceded that Abu Zubaydah was skeptical of the plot and thought it unfeasible, but nonetheless the Justice Department emphasized a dire potential and the threat posed by Padilla as reality106.

Binyam and Padilla met with KSM and his contingent in Karachi107. Having received verbal and written assurances from Abu Zubaydah about the two operatives108, KSM was forced to admit that their hypothetical radiation bomb was mythical109. He instead discussed soft target attacks to destabilize American security, with aims at hotels or gas stations110, before reverting to Atef’s natural gas based high-rise apartment explosions, when the two balked111. Padilla was also unwilling to conduct a martyrdom operation. KSM and Ammar al-Baluchi detailed the high-rise plot to the prospects and expected to have two readied operatives in America, one by direct travel, and Binyam once he had obtained proper documents in Britain112. Baluchi facilitated their travel and communications for them beginning in March113. Further, both Ramzi Binalshibh and Shukrijumah prepared them for mobilization with important information on fraudulent travel documents and coded communications114.

In early April, KSM along with Binalshibh and Ahmed Ghulam Rabbani dined at a Karachi establishment, where they were joined by Ammar al-Baluchi, Padilla, and Binyam115. There at the restaurant, KSM delivered approximately $5,000 to the pair for operational usage, still believing Padilla to be an adequate enabler of external missions116. Padilla had already received $10,000 from Baluchi and a cellular phone117. The next day they were to depart, protected by their training118.

Yet the training was insufficient and on that early April day they were both detained by Pakistani airport security119. KSM was undeterred and deployed them for a second attempt, but Binyam was caught in various lies during his inevitable detention, resulting in his being transferred to Pakistani ISI custody120. He was rendered to Morocco for 18 months, before arriving in CIA custody in January 2004, where he remained for over 110 days, at a CIA Detention Site and at Bagram Airbase121. In September, Binyam finally ended his journey in Guantanamo as ISN 1458122.

With Abu Zubaydah under interrogation, the details of Padilla and Binyam (excluding their actual names) became known to the Americans. This was in part due to a captured copy of Abu Zubaydah’s letter of recommendation concerning Padilla, whom he described as a capable Argentine123. But Padilla’s misadventure on April 4 had already caused Pakistani and American authorities to link the suspicious American traveler to a mysterious suspected operative124. Padilla’s passport information obtained from the Pakistani detention, including a date of birth of October 18, 1970, matched the relevant categories of the “Mujahadin Identification Form,” now in FBI custody125. About a week later, Abu Zubaydah’s tale of the radioactive bomb emerged, after authorities presented the Palestinian with the letter and the knowledge that he had deployed two operatives126. On April 20, the stories were finally connected and an advisory issued for the American127.

Padilla meanwhile, successfully made his way to Zurich, Switzerland and then on to Cairo to visit his family128. When he returned to America on May 8, landing at O’Hare International in Chicago, he was joined on the aircraft surreptitiously by federal agents, now aware of his identity129. Apprehended in the airport, Padilla was detained on uncertain grounds, before being named an enemy combatant and being transferred from the Justice Department to military custody in June130. After being declared an enemy combatant, the Attorney General sensationalized the case, focusing on the elements regarding the dirty bomb131. Padilla was then incarcerated in solitary confinement in a US Naval brig in Charleston, SC132. As an enemy combatant, he was assigned the ISN 10008133. It is not certain that Padilla would have ever carried out a mission, or if his endgame was simply to escape Afghanistan and Pakistan safely.

Pride and Exasperation

Even as the Americans were unmasking Padilla, KSM and his men continued to act recklessly. From April 19-21, he and Ramzi Binalshibh hosted an al-Jazeera journalist, allowed themselves to be videotaped, and proclaimed responsibility as coordinators of the 9/11 attacks134. This was just over a week from the Djerba, Tunisia bombing. The journalist, Yosri Fouda, was covertly brought to a safehouse and given instructions on what to say afterwards135. KSM was particular in his appearance and statements, and purportedly went as far as to name himself the head of al-Qaida’s Military Committee136. This could be evidence of an inflated self view embodied by KSM, inaccurate translation, or even simple assumption due to the loss of Atef in Kabul and the distance (and eventual detention) of Saif al-Adel in Iran. KSM later denied claiming this particular title to the journalist137. Regardless, during their time together, KSM provided a statement to Fouda regarding the Djerba attack, a supposed documentary, the will of a 9/11 hijacker, and video evidence of the Daniel Pearl murder138. The two wanted men insinuated that they displayed restraint in not striking American nuclear targets on 9/11, and that they had no dearth of readied suicidal operatives139. Proudly, they even accepted the appellation of terrorists140.

That KSM delivered Fouda these cassettes and evidence proved that in addition to operational planning, he also did not shirk his media concerns. He tasked Ammar al-Baluchi to coordinate with other operatives in the production of such videos. Baluchi delved into the media campaign endeavoring with Abu Talha al-Pakistani on this front in Karachi, in order for the products to be viewed in the West141. They established contact with al-Jazeera representatives in Qatar through which they eventually published two al-Qaida videos as part of the KSM media commitment142. These included the titles “Why We Fight,” which Baluchi also distributed online to operative Yusef al-Ayiri in Saudi Arabia143 –[B]. The second was the “9/11 Anniversary” video, which was developed alongside Abu Faraj al-Libi and maintained for the occasion later in 2002144 –[C]. Coordination between these departments of al-Qaida (those based in either rural tribal agencies or urban centers like Karachi) was again demonstrated as Baluchi and senior as-Sahab media operative Abu Abdulrahman al-Maghrebi145 combined portions of the video to create the finalized version146. This included wills of the martyrs section, which contained 9/11 hijacker martyrdom statements147. They delivered the video to KSM nephew Abu Musab al-Baluchi and he ensured its retrieval by al-Jazeera in Islamabad148. Clearly displayed by the interviews and media products, the KSM contingent was not lacking in confidence. Interestingly, the interview also emphasized that despite the work of his own nephews, KSM relied heavily upon Binalshibh.

By June, KSM considered Binalshibh his confidant and lieutenant due to the latter’s successful perpetration of his role in the 9/11 operation149. As such KSM began to plot with and run ideas through the Yemeni. Among those that they considered was a potential hijacking from Heathrow Airport, where the aircraft would then be crashed into the busy airport itself150. Binalshibh recommended embedding al-Qaida operatives among Heathrow employees in addition to actual hijackers151. Ammar al-Baluchi also later participated in the plotting of this venture152. Later, in November, KSM assigned operative Abu Talha al-Pakistani to surveil the airport, and the ideas grew ever more fanciful, including multiple aircraft, and diversionary explosions153. Abu Talha traveled to Britain multiple times for the casings154. However, the plan was overly ambitious, and KSM was formulating the plans faster than he could successfully complete any, or provide security for his operatives. These included plots to assassinate former US President Carter, plummet hijacked Saudi aircraft into Israel, bomb US and Israeli embassies across the globe, and strike American military bases and concentrations of soldiers in South Korea155.

KSM had inherited other advanced plots and further operatives. This included a subset under senior COLE bomber Abdulrahim al-Nashiri, who was tasked after his success, with attacking oil tankers in the Strait of Hormuz with bomb-laden watercraft156. KSM oversaw Nashiri on multifarious methods and plots within the Arabian Peninsula and assigned him a competent contingent of militants being facilitated homeward157. These included the KSM appointed paramilitary commander for insurgent operations in Saudi Arabia under Nashiri: the fearsome Abdulaziz al-Muqrin158 – [B]. KSM and Nashiri coordinated these personnel assignments while the latter was still in Karachi159. To liaise between the two echelons while Nashiri was deployed to Arabia, KSM assigned the established facilitator Badr Abdulkarim al-Sudayri, known as Abu Zubair al-Haili, who was respected for his time in Afghanistan as the administrator of the Hajji Habash militant guesthouse in Kandahar160. For the Strait of Hormuz ambition, Nashiri committed al-Faruq instructor Ahmed al-Darbi to helm161. He and Darbi reported up to KSM on the status of the plot, and KSM allowed them to use one of his own men for tasking162. To complete the action, Nashiri dispatched al-Qaida facilitator Ahmed Ghulam Rabbani to the UAE in order to purchase an adequate boat163. Ahmed also cased the port of Karachi in order to assist Nashiri with further potential maritime strikes164. Despite having possession of the boat, explosives, and men provided by Nashiri, Darbi failed and was apprehended in June 2002 abroad, before being transferred to Guantanamo165. Nashiri even attempted to enact an unsanctioned similar attack, against US and British naval vessels in the Strait of Gibraltar, but this too faltered when the operatives were captured in Morocco the same month166. In fact, the KSM liaison Badr al-Sudayri was also apprehended in Morocco, with American authorities praising the event with an inflated assessment of the 300 pound operative’s worth167. KSM chastised Nashiri for the actions, but was himself the recipient of a letter of reprimand from Saif al-Adel in June 2002168.

Obviously, Adel was fatigued with failure and the bluster of KSM. Adel was adamant that KSM should cease his focus on external operations and, as Saif al-Adel put it, stop sending their men into nothing other than captivity169. It is here that Saif al-Adel ventured into insubordination, declaring to KSM to disregard all orders concerning external operation, even if they are from bin Laden170. In the eyes of Saif al-Adel, their jihadist followers had lost respect and confidence in al-Qaida, openly wondering how they could have failed in their follow up operations, even when they were utilizing pious and righteous operatives171. Thus Saif al-Adel wanted KSM to regroup and rethink going forward. Their men should not be wasted on KSM developed plots, but should be utilized in other respects172. Furthermore, Saif al-Adel wished for KSM to cease all management responsibilities and slowly transfer them to the cadre of Iran based al-Qaida members, most predominantly the Egyptian Shura members173. For matters in northern Afghanistan, Adel wanted Abdulhadi al-Iraqi in charge, and for all matters concerning Pakistan and the remainder of Afghanistan, he desired promoting Abu Faraj al-Libi for the duty174. The letter was for naught, and bin Laden wished for KSM to remain at his post. Nashiri for his part, only added to the onslaught of misfortune, allowing himself to be captured in the UAE later in November175. Thus, KSM was robbed of capable leadership and directly linked operatives in the Peninsula. COLE and 9/11 conspirator Walid bin Attash next assumed responsibility for the region, but he did so from afar as he too was based in Karachi with his superiors176.

Early Safety Compromised

There were other examples of misfortunes, as the Karachi safehouse network was not immune from casualties either. As mentioned, The Madafat Riyadh house was under the control of Riyadh the Facilitator177, the alias of Abdah Ali al-Hajj al-Sharqawi178; and the Yemeni assisted over 100 fleeing jihadists return to their home nations179. Perhaps more importantly, he facilitated the moving and utilizing of funds in excess of half a million dollars180. Nashiri was known to use the Madafat Riyadh as his initial operational base, and KSM emerged from the shadows of war and returned to Karachi at this locale in January 2002181. However, KSM, Nashiri, and their men apparently only utilized the home briefly before settling into other established bases; or, as in the the case of Nashiri, deploying onward. Sharqawi diligently continued work, and received at least $100,000 from affluent Saudis for the cause182. He was initially forwarding large sums of cash via Afghan couriers to militants in Afghanistan183. Eventually, these types of fund transfers with physical cash were deemed unfeasible184. From this location, Sharqawi worked closely with other facilitators in the transfers of logistical supplies185. This was not just for the war theatre, but for operational concerns also. For example, he participated in forwarding at least $20,000 to an Egyptian contact in Somalia, with the funds believed to have been used for attacks in Mombasa, Kenya later in the year186. Early in the post-invasion era, on February 7, 2002, the safehouse was raided by the Pakistani ISI and American authorities resulting in Sharqawi’s capture, along with at least 14 other foreign fighters187. Sharqawi was not transferred to CIA custody until January 2004, as he was first rendered to Jordan188. After time in a CIA Detention Site and Bagram Airbase, he was transported to Guantanamo in May 2004, as ISN 1457189.

Several of those captured were awaiting their facilitation homeward, with Sharqawi ensuring that they obtain passports, for example190. Some had retreated to Pakistan from the battle of Tora Bora191. Generally, they were all displacing from the war zone. Those apprehended included nine Yemenis, two Kuwaitis, and one each of Saudi, Russian, and British citizenship192 – [D]. The Brit was Richard Dean Belmar of London, a recent convert to Islam, who desperately tried to flee Afghanistan once the invasion commenced, but whose escape culminated in the Madafat Riyadh193. Americans investigating the Daniel Pearl beheading thought Belmar might be a candidate to work covertly for MI5, but the relevant British agents refused the idea194. Thus, Belmar, an absolute insignificant party, was stranded to languish in American custody at Bagram and Guantanamo195. One of the Yemenis was Zuhail al-Sharabi, known as Abu Bara’a al-Yemeni or Abu Bara al-Taizi196. Sharabi was a sworn member of bin Laden’s security detachment and veteran of Brigade 55197. Chosen specifically by bin Laden to partake in the 9/11 plot as a suicide operative, the task was deemed dubious due to his inability to acquire a US visa198. Thus, his role evolved into the proposed Southeast Asia portion of the operation, which was itself eventually cancelled due to complexities199. The Yemeni traveled with Walid bin Attash to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia around the turn of the century in order to case flights, targets, and to participate in the infamous al-Qaida summit there with eventual 9/11 hijackers Khalid al-Mihdhar and Nawaf al-Hazmi200. His role faded to obscurity afterwards, until his arrest at the Madafat Riyadh.

Even with successive failures, the loss of Abu Zubaydah, the stressful oversight from Saif al-Adel, the compromise of the Karachi safehouses, and the evidently risky media endeavors, KSM was strained but not defeated; and thus, remained confident. The latter half of 2002 saw KSM pursue further attacks, including both targets abroad and some within his own immediate vicinity.

CITATIONS and SUBSTANTIVE NOTES:

- [A] Judi identified the eight other militants originally in Mirwais with him by their aliases, naming them as Abu Waqas (Awaith), Abu Dujanah (al-Makki), Abu Ammar, Abu Thuwab, Abu Habib, Abu Bakr, Abu Hammam, and Abu Sahib201. The US government later presented evidence that in addition to Abu Waqas, four of the militants received advanced training at Tarnak Farms: Abu Sahib, Abu Bakr, Abu Ammar, and Abu Dujanah202.

- [B] In addition, KSM assigned the Yemeni Khalid al-Hajj and the Saudi Ali al-Faqasi al-Ghamdi to vital leadership and logistical roles in Nashiri’s nexus, among other specifically selected individuals – For more on Nashiri, Darbi, Muqrin, Yusef al-Ayiri, Hajj, Ghamdi, and multiple others operating in the Arabian Peninsula at the time, please see the Series: Fugitives of the Peninsula: https://chroniclesinzealotry.com/fugitives-of-the-peninsula/

- [C] That Abu Faraj was coordinating on this type of media project early in 2002, well before his official appointment as commander of internal operations, indicates that he was already well entrenched in these duties, as is seen by some scholars. Plus, Saif al-Adel all but confirms this in demanding that all Pakistani issues pass from KSM to Abu Faraj in June 2002.

- [D] An apparent fifteen of the apprehended individuals were eventually taken to Guantanamo, with Sharqawi as ISN 1457, Belmar as ISN 817, Sharabi as ISN 569, and the remainder as ISNs 564, 565, 566, 568, 570, 571, 572, 573, 574, 575, 576, and 578.

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Majid Abdullah al-Judi, ISN 25, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/25.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Majid Abdullah al-Judi, ISN 25, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/25.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Majid Abdullah al-Judi, ISN 25, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/25.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Majid Abdullah al-Judi, ISN 25, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/25.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Majid Abdullah al-Judi, ISN 25, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/25.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Majid Abdullah al-Judi, ISN 25, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/25.html ↩︎

- Al-Qaida Holdouts Killed in Hospital, by Ellen Knickmeyer, The Associated Press, January 27, 2002 ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Majid Abdullah al-Judi, ISN 25, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/25.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Majid Abdullah al-Judi, ISN 25, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/25.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Majid Abdullah al-Judi, ISN 25, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/25.html ↩︎

- Al-Qaida Holdouts Killed in Hospital, by Ellen Knickmeyer, The Associated Press, January 27, 2002 // Kandahar Hospital Siege Ends in Al Qaeda Deaths, by Pamela Constable, The Washington Post, January 28, 2002, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2002/01/29/kandahar-hospital-siege-ends-in-al-qaeda-deaths/1ad51464-a2b5-4a10-b31d-dcdb85737ca6/ ↩︎

- Al-Qaida Holdouts Killed in Hospital, by Ellen Knickmeyer, The Associated Press, January 27, 2002 ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Adam Mohamed Ali al-Awaith, ISN 88, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/88.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Adam Mohamed Ali al-Awaith, ISN 88, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/88.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Adam Mohamed Ali al-Awaith, ISN 88, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/88.html ↩︎

- Adham Mohammed Ali Awad v Barack H. Obama, et al, United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, March 19, 2010, https://2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/179310.pdf ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Majid Abdullah al-Judi, ISN 25, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/25.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Majid Abdullah al-Judi, ISN 25, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/25.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Majid Abdullah al-Judi, ISN 25, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/25.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Adam Mohamed Ali al-Awaith, ISN 88, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/88.html ↩︎

- Al-Qaida Holdouts Killed in Hospital, by Ellen Knickmeyer, The Associated Press, January 27, 2002 ↩︎

- Al-Qaida Holdouts Killed in Hospital, by Ellen Knickmeyer, The Associated Press, January 27, 2002 ↩︎

- Al-Qaida Holdouts Killed in Hospital, by Ellen Knickmeyer, The Associated Press, January 27, 2002 ↩︎

- Kandahar Hospital Siege Ends in Al Qaeda Deaths, by Pamela Constable, The Washington Post, January 28, 2002, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2002/01/29/kandahar-hospital-siege-ends-in-al-qaeda-deaths/1ad51464-a2b5-4a10-b31d-dcdb85737ca6/ ↩︎

- Kandahar Hospital Siege Ends in Al Qaeda Deaths, by Pamela Constable, The Washington Post, January 28, 2002, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2002/01/29/kandahar-hospital-siege-ends-in-al-qaeda-deaths/1ad51464-a2b5-4a10-b31d-dcdb85737ca6/ ↩︎

- Kandahar Hospital Siege Ends in Al Qaeda Deaths, by Pamela Constable, The Washington Post, January 28, 2002, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2002/01/29/kandahar-hospital-siege-ends-in-al-qaeda-deaths/1ad51464-a2b5-4a10-b31d-dcdb85737ca6/ ↩︎

- Al-Qaida Holdouts Killed in Hospital, by Ellen Knickmeyer, The Associated Press, January 27, 2002 ↩︎

- Kandahar Hospital Siege Ends in Al Qaeda Deaths, by Pamela Constable, The Washington Post, January 28, 2002, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2002/01/29/kandahar-hospital-siege-ends-in-al-qaeda-deaths/1ad51464-a2b5-4a10-b31d-dcdb85737ca6/ ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Majid Abdullah al-Judi, ISN 25, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/25.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Majid Abdullah al-Judi, ISN 25, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/25.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Majid Abdullah al-Judi, ISN 25, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/25.html // Guantanamo Assessment File, Adam Mohamed Ali al-Awaith, ISN 88, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/88.html ↩︎

- Kandahar Hospital Siege Ends in Al Qaeda Deaths, by Pamela Constable, The Washington Post, January 28, 2002, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2002/01/29/kandahar-hospital-siege-ends-in-al-qaeda-deaths/1ad51464-a2b5-4a10-b31d-dcdb85737ca6/ ↩︎

- Kandahar Hospital Siege Ends in Al Qaeda Deaths, by Pamela Constable, The Washington Post, January 28, 2002, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2002/01/29/kandahar-hospital-siege-ends-in-al-qaeda-deaths/1ad51464-a2b5-4a10-b31d-dcdb85737ca6/ ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Majid Abdullah al-Judi, ISN 25, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/25.html ↩︎

- Kashmiri’s Arrest to Put Pressure on Pakistan, Dawn, June 21, 2003, https://www.dawn.com/news/107508/kashmiri-s-arrest-to-put-pressure-on-pakistan ↩︎

- United States District Court, Southern District of Illinois, United States of America vs Iyman Faris, previously known as Mohamed Rauf, Plaintiff’s Motion for Summary Judgment and Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support ↩︎

- United States District Court, Southern District of Illinois, United States of America vs Iyman Faris, previously known as Mohamed Rauf, Plaintiff’s Motion for Summary Judgment and Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support ↩︎

- United States District Court, Southern District of Illinois, United States of America vs Iyman Faris, previously known as Mohamed Rauf, Plaintiff’s Motion for Summary Judgment and Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support ↩︎

- United States District Court, Southern District of Illinois, United States of America vs Iyman Faris, previously known as Mohamed Rauf, Plaintiff’s Motion for Summary Judgment and Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support ↩︎

- Iyman Faris Sentenced for Providing Material Support to Al Qaeda, US Department of Justice Press Release, October 28, 2003, https://www.justice.gov/archive/opa/pr/2003/October/03_crm_589.htm ↩︎

- Iyman Faris Sentenced for Providing Material Support to Al Qaeda, US Department of Justice Press Release, October 28, 2003, https://www.justice.gov/archive/opa/pr/2003/October/03_crm_589.htm ↩︎

- Iyman Faris Sentenced for Providing Material Support to Al Qaeda, US Department of Justice Press Release, October 28, 2003, https://www.justice.gov/archive/opa/pr/2003/October/03_crm_589.htm ↩︎

- Iyman Faris Sentenced for Providing Material Support to Al Qaeda, US Department of Justice Press Release, October 28, 2003, https://www.justice.gov/archive/opa/pr/2003/October/03_crm_589.htm ↩︎

- Kashmiri’s Arrest to Put Pressure on Pakistan, Dawn, June 21, 2003, https://www.dawn.com/news/107508/kashmiri-s-arrest-to-put-pressure-on-pakistan ↩︎

- Trucker Sentenced to 20 Years in Plot Against Brooklyn Bridge, by Eric Lichtblau, The New York Times, October 29, 2003, https://www.nytimes.com/2003/10/29/us/trucker-sentenced-to-20-years-in-plot-against-brooklyn-bridge.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Khalid Sheikh Mohamed, ISN 10024, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10024.html // Iyman Faris Sentenced for Providing Material Support to Al Qaeda, US Department of Justice Press Release, October 28, 2003, https://www.justice.gov/archive/opa/pr/2003/October/03_crm_589.htm ↩︎

- Al Qaeda In America: The Enemy Within, by Evan Thomas, Newsweek, June 22, 2003, https://www.newsweek.com/al-qaeda-america-enemy-within-138085 ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Khalid Sheikh Mohamed, ISN 10024, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10024.html // Iyman Faris Sentenced for Providing Material Support to Al Qaeda, US Department of Justice Press Release, October 28, 2003, https://www.justice.gov/archive/opa/pr/2003/October/03_crm_589.htm ↩︎

- Iyman Faris Sentenced for Providing Material Support to Al Qaeda, US Department of Justice Press Release, October 28, 2003, https://www.justice.gov/archive/opa/pr/2003/October/03_crm_589.htm ↩︎

- Iyman Faris Sentenced for Providing Material Support to Al Qaeda, US Department of Justice Press Release, October 28, 2003, https://www.justice.gov/archive/opa/pr/2003/October/03_crm_589.htm ↩︎

- Iyman Faris Sentenced for Providing Material Support to Al Qaeda, US Department of Justice Press Release, October 28, 2003, https://www.justice.gov/archive/opa/pr/2003/October/03_crm_589.htm ↩︎

- Iyman Faris Sentenced for Providing Material Support to Al Qaeda, US Department of Justice Press Release, October 28, 2003, https://www.justice.gov/archive/opa/pr/2003/October/03_crm_589.htm ↩︎

- Terror Suspect’s Path from Streets to Brig, by Deborah Sontag, The New York Times, April 25, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/25/us/terror-suspect-s-path-from-streets-to-brig.html ↩︎

- Terror Suspect’s Path from Streets to Brig, by Deborah Sontag, The New York Times, April 25, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/25/us/terror-suspect-s-path-from-streets-to-brig.html ↩︎

- Terror Suspect’s Path from Streets to Brig, by Deborah Sontag, The New York Times, April 25, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/25/us/terror-suspect-s-path-from-streets-to-brig.html ↩︎

- Terror Suspect’s Path from Streets to Brig, by Deborah Sontag, The New York Times, April 25, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/25/us/terror-suspect-s-path-from-streets-to-brig.html ↩︎

- Terror Suspect’s Path from Streets to Brig, by Deborah Sontag, The New York Times, April 25, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/25/us/terror-suspect-s-path-from-streets-to-brig.html ↩︎

- Terror Suspect’s Path from Streets to Brig, by Deborah Sontag, The New York Times, April 25, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/25/us/terror-suspect-s-path-from-streets-to-brig.html ↩︎

- Terror Suspect’s Path from Streets to Brig, by Deborah Sontag, The New York Times, April 25, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/25/us/terror-suspect-s-path-from-streets-to-brig.html ↩︎

- Terror Suspect’s Path from Streets to Brig, by Deborah Sontag, The New York Times, April 25, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/25/us/terror-suspect-s-path-from-streets-to-brig.html ↩︎

- Terror Suspect’s Path from Streets to Brig, by Deborah Sontag, The New York Times, April 25, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/25/us/terror-suspect-s-path-from-streets-to-brig.html ↩︎

- Terror Suspect’s Path from Streets to Brig, by Deborah Sontag, The New York Times, April 25, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/25/us/terror-suspect-s-path-from-streets-to-brig.html // Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf ↩︎

- Terror Suspect’s Path from Streets to Brig, by Deborah Sontag, The New York Times, April 25, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/25/us/terror-suspect-s-path-from-streets-to-brig.html ↩︎

- Remarks of Deputy Attorney General James Comey Regarding Jose Padilla

Tuesday, June 1, 2004, https://www.justice.gov/archive/dag/speeches/2004/dag6104.htm // Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf ↩︎ - Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf ↩︎

- Remarks of Deputy Attorney General James Comey Regarding Jose Padilla

Tuesday, June 1, 2004, https://www.justice.gov/archive/dag/speeches/2004/dag6104.htm // Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf ↩︎ - Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf ↩︎

- Remarks of Deputy Attorney General James Comey Regarding Jose Padilla

Tuesday, June 1, 2004, https://www.justice.gov/archive/dag/speeches/2004/dag6104.htm // Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf ↩︎ - Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf // Key Evidence in Padilla Case: An Al Qaeda Job Application, by Jim Avila and Ellen Davis, ABC News, May 14, 2007, https://abcnews.go.com/TheLaw/LegalCenter/story?id=3170794&page=1 // Transcript of the Attorney General John Ashcroft Regarding the transfer of Abdullah Al Muhajir (Born Jose Padilla) To the Department of Defense as an Enemy Combatant, June 10, 2002, https://www.justice.gov/archive/ag/speeches/2002/061002agtranscripts.htm ↩︎

- Key Evidence in Padilla Case: An Al Qaeda Job Application, by Jim Avila and Ellen Davis, ABC News, May 14, 2007, https://abcnews.go.com/TheLaw/LegalCenter/story?id=3170794&page=1 // Remarks of Deputy Attorney General James Comey Regarding Jose Padilla

Tuesday, June 1, 2004, https://www.justice.gov/archive/dag/speeches/2004/dag6104.htm ↩︎ - CIA Officer Testifies He Was Given Qaeda ‘Pledge Form’ Said To Be Padilla’s, by Abby Goodnough, The New York Times, May 16, 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/16/us/16padilla.html // Key Evidence in Padilla Case: An Al Qaeda Job Application, by Jim Avila and Ellen Davis, ABC News, May 14, 2007, https://abcnews.go.com/TheLaw/LegalCenter/story?id=3170794&page=1 ↩︎

- CIA Officer Testifies He Was Given Qaeda ‘Pledge Form’ Said To Be Padilla’s, by Abby Goodnough, The New York Times, May 16, 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/16/us/16padilla.html //Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Remarks of Deputy Attorney General James Comey Regarding Jose Padilla

Tuesday, June 1, 2004, https://www.justice.gov/archive/dag/speeches/2004/dag6104.htm // Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf ↩︎ - Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf ↩︎

- Remarks of Deputy Attorney General James Comey Regarding Jose Padilla

Tuesday, June 1, 2004, https://www.justice.gov/archive/dag/speeches/2004/dag6104.htm // Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf ↩︎ - Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf ↩︎

- Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf ↩︎

- Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf ↩︎

- Remarks of Deputy Attorney General James Comey Regarding Jose Padilla

Tuesday, June 1, 2004, https://www.justice.gov/archive/dag/speeches/2004/dag6104.htm ↩︎ - Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf ↩︎

- Remarks of Deputy Attorney General James Comey Regarding Jose Padilla

Tuesday, June 1, 2004, https://www.justice.gov/archive/dag/speeches/2004/dag6104.htm ↩︎ - Remarks of Deputy Attorney General James Comey Regarding Jose Padilla

Tuesday, June 1, 2004, https://www.justice.gov/archive/dag/speeches/2004/dag6104.htm ↩︎ - Remarks of Deputy Attorney General James Comey Regarding Jose Padilla

Tuesday, June 1, 2004, https://www.justice.gov/archive/dag/speeches/2004/dag6104.htm ↩︎ - Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf ↩︎

- Remarks of Deputy Attorney General James Comey Regarding Jose Padilla

Tuesday, June 1, 2004, https://www.justice.gov/archive/dag/speeches/2004/dag6104.htm ↩︎ - Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎

- Remarks of Deputy Attorney General James Comey Regarding Jose Padilla

Tuesday, June 1, 2004, https://www.justice.gov/archive/dag/speeches/2004/dag6104.htm // Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎ - Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Remarks of Deputy Attorney General James Comey Regarding Jose Padilla

Tuesday, June 1, 2004, https://www.justice.gov/archive/dag/speeches/2004/dag6104.htm ↩︎ - Remarks of Deputy Attorney General James Comey Regarding Jose Padilla

Tuesday, June 1, 2004, https://www.justice.gov/archive/dag/speeches/2004/dag6104.htm // Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎ - Remarks of Deputy Attorney General James Comey Regarding Jose Padilla

Tuesday, June 1, 2004, https://www.justice.gov/archive/dag/speeches/2004/dag6104.htm ↩︎ - Remarks of Deputy Attorney General James Comey Regarding Jose Padilla

Tuesday, June 1, 2004, https://www.justice.gov/archive/dag/speeches/2004/dag6104.htm // Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎ - Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎

- Remarks of Deputy Attorney General James Comey Regarding Jose Padilla

Tuesday, June 1, 2004, https://www.justice.gov/archive/dag/speeches/2004/dag6104.htm // Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎ - Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Ali Abdulaziz Ali, (Ammar al-Baluchi), ISN 10018, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10018.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Ramzi Binalshibh, ISN 10013, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10013.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Ramzi Binalshibh, ISN 10013, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10013.html ↩︎

- Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf ↩︎

- Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎

- CIA Torture Unredacted: An Investigation Into the CIA Torture Programme, Sam Raphael, Crofton Black, Ruth Blakely, The Rendition Project, https://www.therenditionproject.org.uk/documents/RDI/190710-TRP-TBIJ-CIA-Torture-Unredacted-Full.pdf // Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎

- CIA Torture Unredacted: An Investigation Into the CIA Torture Programme, Sam Raphael, Crofton Black, Ruth Blakely, The Rendition Project, https://www.therenditionproject.org.uk/documents/RDI/190710-TRP-TBIJ-CIA-Torture-Unredacted-Full.pdf // Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- CIA Torture Unredacted: An Investigation Into the CIA Torture Programme, Sam Raphael, Crofton Black, Ruth Blakely, The Rendition Project, https://www.therenditionproject.org.uk/documents/RDI/190710-TRP-TBIJ-CIA-Torture-Unredacted-Full.pdf //Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Terror Suspect’s Path from Streets to Brig, by Deborah Sontag, The New York Times, April 25, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/25/us/terror-suspect-s-path-from-streets-to-brig.html // Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf ↩︎

- Terror Suspect’s Path from Streets to Brig, by Deborah Sontag, The New York Times, April 25, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/25/us/terror-suspect-s-path-from-streets-to-brig.html // Summary of Jose Padilla’s Activities with Al Qaeda, https://irp.fas.org/news/2004/06/padilla060104.pdf // Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Transcript of the Attorney General John Ashcroft Regarding the transfer of Abdullah Al Muhajir (Born Jose Padilla) To the Department of Defense as an Enemy Combatant, June 10, 2002, https://www.justice.gov/archive/ag/speeches/2002/061002agtranscripts.htm // Terror Suspect’s Path from Streets to Brig, by Deborah Sontag, The New York Times, April 25, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/25/us/terror-suspect-s-path-from-streets-to-brig.html ↩︎

- Transcript of the Attorney General John Ashcroft Regarding the transfer of Abdullah Al Muhajir (Born Jose Padilla) To the Department of Defense as an Enemy Combatant, June 10, 2002, https://www.justice.gov/archive/ag/speeches/2002/061002agtranscripts.htm ↩︎

- Terror Suspect’s Path from Streets to Brig, by Deborah Sontag, The New York Times, April 25, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/25/us/terror-suspect-s-path-from-streets-to-brig.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Binyam Ahmed Mohamed, ISN 1458, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1458.html ↩︎

- ‘We left out nuclear targets, for now’, by Yosri Fouda, The Guardian, March 3, 2003, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/mar/04/alqaida.terrorism ↩︎

- ‘We left out nuclear targets, for now’, by Yosri Fouda, The Guardian, March 3, 2003, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/mar/04/alqaida.terrorism ↩︎

- ‘We left out nuclear targets, for now’, by Yosri Fouda, The Guardian, March 3, 2003, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/mar/04/alqaida.terrorism ↩︎

- Verbatim Transcript of Combatant Status Review Tribunal Hearing for ISN 10024, March 10, 2007, https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/FOID/Reading%20Room/Detainne_Related/15-L-1645_CSRT%20Transcript%20ISN%2010024_10-mar-07.pdf ↩︎

- ‘We left out nuclear targets, for now’, by Yosri Fouda, The Guardian, March 3, 2003, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/mar/04/alqaida.terrorism ↩︎

- ‘We left out nuclear targets, for now’, by Yosri Fouda, The Guardian, March 3, 2003, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/mar/04/alqaida.terrorism ↩︎

- ‘We left out nuclear targets, for now’, by Yosri Fouda, The Guardian, March 3, 2003, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/mar/04/alqaida.terrorism ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Ali Abdulaziz Ali, (Ammar al-Baluchi), ISN 10018, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10018.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Ali Abdulaziz Ali, (Ammar al-Baluchi), ISN 10018, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10018.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Ali Abdulaziz Ali, (Ammar al-Baluchi), ISN 10018, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10018.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Ali Abdulaziz Ali, (Ammar al-Baluchi), ISN 10018, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10018.html ↩︎

- Abd al-Rahman al-Maghrebi, Rewards for Justice profile, https://rewardsforjustice.net/rewards/abd-al-rahman-al-maghrebi/ ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Ali Abdulaziz Ali, (Ammar al-Baluchi), ISN 10018, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10018.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Ali Abdulaziz Ali, (Ammar al-Baluchi), ISN 10018, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10018.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Ali Abdulaziz Ali, (Ammar al-Baluchi), ISN 10018, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10018.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Ramzi Binalshibh, ISN 10013, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10013.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Ramzi Binalshibh, ISN 10013, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10013.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Ramzi Binalshibh, ISN 10013, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10013.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Ali Abdulaziz Ali, (Ammar al-Baluchi), ISN 10018, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10018.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Ali Abdulaziz Ali, (Ammar al-Baluchi), ISN 10018, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10018.html ↩︎

- Pakistan sniffs out trail of al-Qaida, by Paul Haven, The Associated Press, August 7, 2004, https://www.poconorecord.com/story/news/2004/08/07/pakistan-sniffs-out-trail-al/51060239007/ // THE REACH OF WAR: TERROR ALERT; Rounding Up Qaeda Suspects: New Cooperation, New Tensions, New Questions, by Amy Waldman and Eric Lipton, The New York Times, August 17, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/08/17/us/reach-war-terror-alert-rounding-up-qaeda-suspects-new-cooperation-new-tensions.html ↩︎

- Verbatim Transcript of Combatant Status Review Tribunal Hearing for ISN 10024, March 10, 2007, https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/FOID/Reading%20Room/Detainne_Related/15-L-1645_CSRT%20Transcript%20ISN%2010024_10-mar-07.pdf ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdulrahim al-Nashiri, ISN 10015, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10015.html ↩︎

- Path of Blood: The Story of Al-Qaeda’s War on the House of Saud, Thomas Small and Jonathan Hacker, Simon & Schuster UK, 2015 ↩︎

- Path of Blood: The Story of Al-Qaeda’s War on the House of Saud, Thomas Small and Jonathan Hacker, Simon & Schuster UK, 2015 ↩︎

- Path of Blood: The Story of Al-Qaeda’s War on the House of Saud, Thomas Small and Jonathan Hacker, Simon & Schuster UK, 2015 ↩︎

- Path of Blood: The Story of Al-Qaeda’s War on the House of Saud, Thomas Small and Jonathan Hacker, Simon & Schuster UK, 2015 // Guantanamo Assessment File, Ali Ahmed Mohamed al-Razihi, ISN 45, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/45.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Ahmed al-Darbi, ISN 768, http://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/768.html // Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdulrahim al-Nashiri, ISN 10015, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10015.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdulrahim Ghulam Rabbani, ISN 1460, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1460.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdulrahim Ghulam Rabbani, ISN 1460, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1460.html // Guantanamo Assessment File, Ahmed Ghulam Rabbani, ISN 1461, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1461.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Ahmed Ghulam Rabbani, ISN 1461, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1461.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Ahmed al-Darbi, ISN 768, http://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/768.html ↩︎

- US tastes success with arrest of senior al-Qaida suspects, by Matthew Engel, The Guardian, June 19, 2002, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2002/jun/20/usa.september11 // Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdulrahim al-Nashiri, ISN 10015, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10015.html ↩︎

- US tastes success with arrest of senior al-Qaida suspects, by Matthew Engel, The Guardian, June 19, 2002, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2002/jun/20/usa.september11 // Morocco Detainee Linked to al Qaeda, by James Risen, The New York Times, June 19, 2002, https://www.nytimes.com/2002/06/19/world/morocco-detainee-linked-to-qaeda.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdulrahim al-Nashiri, ISN 10015, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10015.html // Saif al-Adel Letter to Khalid Sheikh Mohamed, June 13, 2002 ↩︎

- Saif al-Adel Letter to Khalid Sheikh Mohamed, June 13, 2002 ↩︎

- Saif al-Adel Letter to Khalid Sheikh Mohamed, June 13, 2002 ↩︎

- Saif al-Adel Letter to Khalid Sheikh Mohamed, June 13, 2002 ↩︎

- Saif al-Adel Letter to Khalid Sheikh Mohamed, June 13, 2002 ↩︎

- Saif al-Adel Letter to Khalid Sheikh Mohamed, June 13, 2002 ↩︎

- Saif al-Adel Letter to Khalid Sheikh Mohamed, June 13, 2002 ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdulrahim al-Nashiri, ISN 10015, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10015.html ↩︎

- The Black Banners: The Inside Story of 911 and the War Against Al-Qaeda, Ali Soufan, W.W. Norton and Company, 2011 // Guantanamo Assessment File, Walid bin Attash (Khallad), ISN 10014, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10014.html // Guantanamo Assessment File, Ali Abdulaziz Ali, (Ammar al-Baluchi), ISN 10018, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/10018.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Musab Omar Ali al-Mudwani, ISN 839, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/839.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdu Ali al-Hajj al-Sharqawi, ISN 1457, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1457.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdu Ali al-Hajj al-Sharqawi, ISN 1457, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1457.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdu Ali al-Hajj al-Sharqawi, ISN 1457, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1457.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdu Ali al-Hajj al-Sharqawi, ISN 1457, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1457.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdu Ali al-Hajj al-Sharqawi, ISN 1457, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1457.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdu Ali al-Hajj al-Sharqawi, ISN 1457, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1457.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdu Ali al-Hajj al-Sharqawi, ISN 1457, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1457.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdu Ali al-Hajj al-Sharqawi, ISN 1457, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1457.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdu Ali al-Hajj al-Sharqawi, ISN 1457, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1457.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Abdu Ali al-Hajj al-Sharqawi, ISN 1457, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/1457.html // Guantanamo Assessment File, Jalal Salim Awad, ISN 564, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/564.html ↩︎

- Double Jeopardy: CIA Renditions to Jordan, Human Rights Watch, April 7, 2008, https://www.hrw.org/report/2008/04/07/double-jeopardy/cia-renditions-jordan // Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Double Jeopardy: CIA Renditions to Jordan, Human Rights Watch, April 7, 2008, https://www.hrw.org/report/2008/04/07/double-jeopardy/cia-renditions-jordan // Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Committee Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program, Executive Summary, December 13, 2012 ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Mansur Mohamed Ali al-Qatta, ISN 566, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/566.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Sabri Mohamed Ibrahim al-Qurashi, ISN 570, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/570.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Hamud Hassan Abdullah, ISN 574, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/574.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Richard Dean Belmar, ISN 817, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/817.html // Beatings, sex abuse and torture: how MI5 left me to rot in US jail, by David Rose, The Guardian, February 26, 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2005/feb/27/guantanamo.usa ↩︎

- Beatings, sex abuse and torture: how MI5 left me to rot in US jail, by David Rose, The Guardian, February 26, 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2005/feb/27/guantanamo.usa ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Richard Dean Belmar, ISN 817, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/817.html // Beatings, sex abuse and torture: how MI5 left me to rot in US jail, by David Rose, The Guardian, February 26, 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2005/feb/27/guantanamo.usa ↩︎

- 9/11 Commission Report, Chapter 5: Al Qaeda Aims At The American Homeland, 2004 // Guantanamo Assessment File, Zuhail Abdu Anam Said al-Sharabi, ISN 569, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/569.html ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Zuhail Abdu Anam Said al-Sharabi, ISN 569, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/569.html // 9/11 Commission Report, Chapter 5: Al Qaeda Aims At The American Homeland, 2004 ↩︎

- 9/11 Commission Report, Chapter 5: Al Qaeda Aims At The American Homeland, 2004 ↩︎

- Guantanamo Assessment File, Zuhail Abdu Anam Said al-Sharabi, ISN 569, https://wikileaks.org/gitmo/prisoner/569.html // 9/11 Commission Report, Chapter 5: Al Qaeda Aims At The American Homeland, 2004 ↩︎

- 9/11 Commission Report, Chapter 5: Al Qaeda Aims At The American Homeland, 2004 ↩︎

- Adham Mohammed Ali Awad v Barack H. Obama, et al, United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, March 19, 2010, https://2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/179310.pdf ↩︎

- Adham Mohammed Ali Awad v Barack H. Obama, et al, United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, March 19, 2010, https://2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/179310.pdf ↩︎

© Copyright 2025 Nolan R Beasley